It’s only a week until we meet in Dublin! I’ve been in Ireland since May 14 travelling with a group of Agnes Scott students, pictured at left on Inch Strand on the Dingle Peninsula. We’ve made our way around Ireland and Northern Ireland visiting literary sites and many other places that are important to history or that are just plain stunningly beautiful. As that trip is winding down, I thought I would post a few miscellaneous items that might be of interest as you prepare to join me here next Sunday.

The student trip is in its fourteenth day, and I can only say I hope our upcoming trip enjoys the same good weather as we’ve had so far. We did have two days of rain, but every other day has been bright, sunny, and a perfect combination of warm and cool. A sweater and a rain coat, jacket or poncho will meet all your weather needs. Though I may be jinxing our trip by saying so, I recommend you bring some sunblock for your face, at least.

I have posted on our site the more or less final version of the itinerary. I say “more or less” because as you know, tweaks and changes—usually to our advantage—are always possible. Please take note of blocks of free time as well as dinners on your own—I can advise to some extent on these, but going online and asking at the hotels are probably your best bets.

I have posted on our site the more or less final version of the itinerary. I say “more or less” because as you know, tweaks and changes—usually to our advantage—are always possible. Please take note of blocks of free time as well as dinners on your own—I can advise to some extent on these, but going online and asking at the hotels are probably your best bets.

The royal wedding last week was surprisingly popular in the Republic of Ireland with many people watching it on TV and talking about it. They did not go so far as to wave Union Jacks as many Unionists in Northern Ireland did, however. Up here (I’m posting this from Belfast), Loyalists held massive tea parties to wish the new couple well, but they seem to have been mainly populated with older people. The wedding was interpreted by many in the Republic as an important step towards modernity by the British monarchy, especially with regard to the multicultural, multiracial aspects of the marriage and the ceremony. In the days surrounding the festivities at Windsor, I have heard a number of people recalling with gratitude Queen Elizabeth’s visit here in 2012, when she made the remarkable choices to say a few words in the Irish language (after centuries of the English trying to stamp out the rebel language) and actually apologize for Britain’s part in the Easter Rising of 1916 and the subsequent War of Independence.

You may have heard of “mummers” via the annual “Mummers Parade” in Philadelphia, but the tradition goes back many hundreds, maybe even many thousands of years in Europe and the Mediterranean world. Mummers are actors in folk plays, usually itinerant, who go from place to place putting on their plays at Christmas and at other sacred times of the year. While their plays do have religious themes, they draw heavily on folk traditions going back to pagan times, often mixing the two, and tend to be irreverent, outrageous, and sometimes bawdy.

A common theme in mummers’ plays is the scarcity of light or sun as the winter season begins and the fear that the sun may never return. This theme is often represented by a death, sometimes of St. George, sometimes of St. Patrick or another well-known figure, followed by attempts at revival and finally a resurrection. The plays include music, songs, dance, poetry, and all manner of entertainment because that is their primary purpose—to entertain the people of a village or manor during the long, cold, dark winter nights. The mummers appear in outlandish costumes, often wearing large basket masks of horse or cow heads and garish clothing. There are many stock figures, including a mysterious doctor wearing a cape with pockets full of “cures,” a pirate, and a man called “Johnny Jack” who “bears his family on his back”—cloth figures that are literally sewn onto his jacket to show that they are his burden. Saint Nicholas often appears, as do knights and ladies, a dragon, an old hag, clown-like characters, and others. The tradition is alive in rural areas of Ireland, and that’s all I will say for now!

As we drive from Dublin to Belfast on June 3, we hope to stop at a place called Monasterboice—a small monastic settlement in the middle of broad green fields in Count Louth—that has three impressive “high crosses,” one of which is said to be the most important in Ireland.

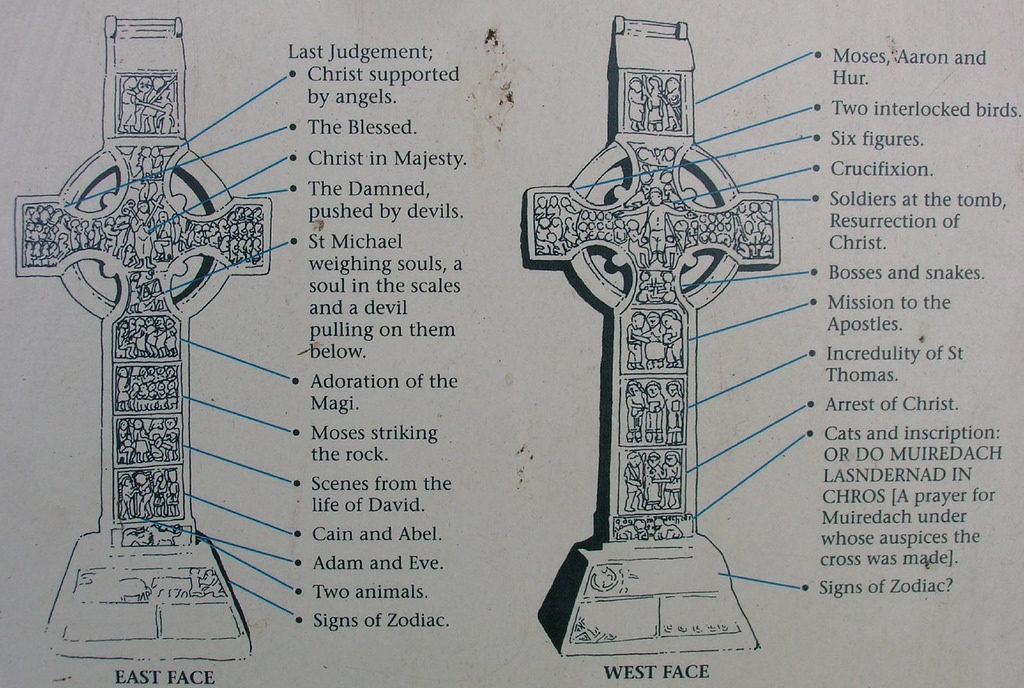

High crosses are found in Ireland and Britain and date from the eighth to tenth centuries CE, though there may have been earlier ones that did not survive. Ireland has so many that they have become an iconic symbol of the country. These crosses stood outside churches or monasteries and were surely built to impress. They served as gathering places and designated markets, but it is likely that they also served as visual aides for the teaching of Christianity through bible stories to a largely illiterate population. Panels on the crosses illustrate key biblical moments: Adam and Eve, the apple tree, and the serpent; Cain striking Abel; Daniel in the lions’ den; the adoration of the magi; the arrest of Christ; the resurrection, etc. I’ve posted a diagram of Muiredach’s cross below (sorry for the image quality, but my resources are limited at the moment).

Interlace patterns decorate the crosses, and there are often personal touches, such as a cat chasing a mouse, a scene from local history, and other secular images. Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, pictured here, is an outstanding example of a high cross. Nineteen feet high and made of sandstone, the cross seems massive compared to the others on the site. The stories carved into its panels are still discernible, though they are gradually becoming effaced by exposure to the elements. Many such crosses have been moved inside with replicas put in their places, or roofed over for protection. For now, Muiredach’s Cross is still in the churchyard and will make an exciting and meaningful detour for us.

Ireland and Europe in general have always been way ahead of the US on the technology used for credit cards. They had chips here long before we did, then chips with PINs (Personal Identifications Numbers—we still don’t have chips with PINs in most cases). Now they are widely using a new system that requires you merely to touch your card to a certain place on the handheld machine—very fast and efficient. Don’t worry, your old-fashioned American card can still be accommodated. There’s always a way to get your money, isn’t there! Just so you know, for some reason American Express cards with chips still often have to be swiped. Visa and MasterCard work fine and are taken nearly everywhere, AMEX less so.

On Friday, the people of Ireland–aided by thousands of Irish men and women who flew home just to vote–voted overwhelmingly to repeal the eighth amendment of their constitution, one of the most severe anti-abortion laws anywhere and an oddity in the European Union. The 1983 amendment allowed no exceptions of any kind and was written in such a way that it caused a long series of tragedies, including women being forced to carry nonviable fetuses to term and sometimes dying in the process. Several recent high profile cases, including that of the death of a 31 -year old woman named Savita Halappanavar, spurred the repeal movement.

This historic vote and others in recent years have shaken loose the conservative Catholic stranglehold on the country (see the this interesting NYT article and this one from today). A series of scandals in churches and church-run schools and institutions over the last several decades–and more to come, no doubt–exposed physical, sexual, financial, and other kinds of abuses–many of them horrific. These breaches of faith have emboldened people to take up issues like the role of women, same-sex marriage, and the eighth amendment and to challenge the power of the church in a society that is increasingly diverse in every way, including religion.

Friday’s vote ended up with 66.4 % saying Yes, 33.7 % saying No, and a turnout that exceeded 64 %. That’s a resounding challenge to the status quo. It’s now up to the Irish house of representatives or Dáil Éireann [DOYL AIR-uhn] to come up with a new law representing the sea change expressed in the vote–no easy task. But the most important achievement in many people’s opinion was the unequivocal message of the people’s desire to separate church and state.