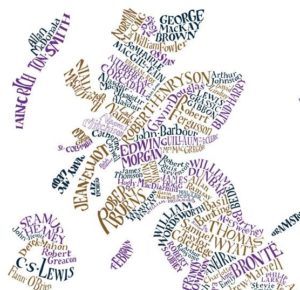

Ireland and Scotland are lands where writers and other creative people thrive. They are inspiring places—their literature is inspiring—and our group trip will be an inspiring experience, so we all need and to have an outlet for our creativity as we travel. Those of you who went on the first trip will remember—with delight, I’m sure—our daily poetry readings at the microphone on the bus, when members of the group, including the group leaders, offer insights and silliness about the trip using the forms of the Limerick, the Haiku, and the six-word essay.

We will of course continue that practice on this trip, with one addition: the Standard Habbie or Burns Stanza. The latter is the first “challenge” offered to you because it is slightly more complex than the others and certainly  less familiar. A long serving form for poetry in Scots, the Standard Habbie found a pace (the “a” lines are in tetrameter or four beats, the “b” lines in dimeter or two beats) that suited the language. Burns took up this form and used it so often and with such distinction that it has come to be called the Burns Stanza.

less familiar. A long serving form for poetry in Scots, the Standard Habbie found a pace (the “a” lines are in tetrameter or four beats, the “b” lines in dimeter or two beats) that suited the language. Burns took up this form and used it so often and with such distinction that it has come to be called the Burns Stanza.

Reading works of our own creation is a fun way to comment on what we are seeing, doing, and experiencing as we roll around the countryside. Your poems and six-word essays should be about the trip; humor and insight always welcome. No literary expertise or even inclination is required. All are welcome to read their offerings, and no one should feel obligated. Below you will find explanations of the four forms, chosen because they are brief and manageable and because they are apt vehicles for humor.

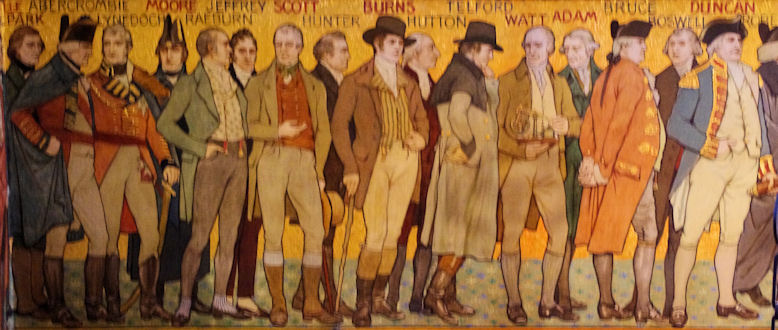

The second challenge will be a challenge to me and my aging brain, as well. Everywhere I went in Burns country I encountered people who could recite passages from his works. When a group of alumnae and friends visited the Burns Cottage in Atlanta recently, the club members who greeted us were impressively versed in Burns’s poems. They even knew all the verses of Auld Lang Syne. So my challenge to you is—memorize a stanza (more always welcome) of a Burns poem that you like and at some point during our trip, recite it at the microphone.

Nothing like memorization to keep the mind nimble! In my father’s day (he was born in 1916) memorization of poetry in school was required and must have been often assigned. He never went to college, but he knew many, many poems by heart. When I told him I was taking Chaucer, he immediately recited the prologue of The Canterbury Tales to me in Middle English:

Nothing like memorization to keep the mind nimble! In my father’s day (he was born in 1916) memorization of poetry in school was required and must have been often assigned. He never went to college, but he knew many, many poems by heart. When I told him I was taking Chaucer, he immediately recited the prologue of The Canterbury Tales to me in Middle English:

Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour….

Come to think of it, we are making a pilgrimage of our own on our bus to literary shrines in both Ireland and Scotland. Who is up for writing an epic poem about our journey?

Later on in graduate school when I mentioned I was writing a paper on Wordsworth’s sonnet “The World Is Too Much With Us,” to my astonishment Dad launched into a recital of that poem, making it all the way to the end without a mistake.

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

I’m afraid that if our last trip is any measure, there will be some “getting and spending” on this one.

I wish I had the ability to hold whole poems and prose passages in my head; it would be a great aid in teaching, but it’s too late now. Still, I plan to challenge myself by memorizing at least a stanza, maybe a whole (short) poem. I hope you will join me. If this little girl named Robyn can do it–Robyn reciting “To A Louse” by Robert Burns–we can, too.

Here are guidelines for the four forms we’ll tackle on the trip.

The Limerick

This well-known humorous verse form has been around since the early 18th century, was popularized by Edward Lear in the 19th century, and is thought to have derived its name from the term “Limerick song,” a kind of drinking song.

Guidelines

- Five-lines

- Anapestic meter: short, short long; – -/; as in “’Twas the night before Christmas and all through the house…

- Rhyme scheme (aaba)

- The first, second and fifth or aaa lines are longer than the bb lines

- Often disturbs normal speech patterns as in “There once was girl from Atlanta…”

- Always funny, often bawdy

Some examples from the previous trip.

Dave has his history down pat

Loves to drive, drink whiskey and chat

He’s the man with the plan

Ready to give us a hand

Now won’t you sleep better knowing dat?

(by Amy Chastain and Wes Cribb)

Which hotel are we in this a.m.?

I need coffee even to begin.

Tripped over the black case,

Fell flat on my face.

Now I’m making coffee again.

(by Margaret Barkley)

The Six-Word Essay

Another contest form for the trip is the six-word essay or narrative, made famous by Ernest Hemingway with this sad tale: “’For sale’ baby shoes, never worn.” We hope your six-word essays won’t be so sad.

Guidelines

- Six words—no cheating!

- The second part usually sheds new light on the first, adding the humor

- Must be true as opposed to fiction

Some examples from the previous trip.

Bags packed. Moving to Muckross House. (by Ellen Gaffney)

Agnes Scott husbands…a lucky lot! (by Jim Jarboe)

Long awaited, anticipated, over too soon! (by Mary K. jarboe)

Haiku

Haiku

Your third option is the haiku, an ancient Japanese poetic form.

Guidelines

- Seventeen syllables

- Three phrases or lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables

- Two images or ideas with a “cutting word” between them to offset the comparison or connection

- Often has a reference to nature

Some examples from the previous trip.

The swans have left Coole.

Empty tower ‘neath the moon.

Still the words endure.

(by Betty Derrick)

Illuminati

A group of vibrant Scotties

Set Dublin aglow.

(by Gwen Shearer)

The Standard Habbie or Burns Stanza

From the online Burns Encyclopedia:

“ The stanza for characteristic of the eighteenth century Revival of Scots poetry, and particularly associated with Burns. But it was also used by Ramsay and Fergusson, and by almost every minor poet who employed Scot. Ramsay called it ‘Standard Habbie’, because the earliest use of it known to him was in ‘Habbie Simpson, the Piper of Kilbarchan’, by Robert Sempill of Beltrees (c.1595-c.i659). The ‘Standard Habbie’ is an easy stanza to write, and was particularly suited for the fast-moving social comment which was a major preoccupation with the writers of the Revival. Burns varied the form by substituting half-rhymes for full rhymes, especially at the ends of the four long lines.”

Guidelines

- Six lines in the stanza

- The rhyme scheme is aaabab

- Tetrameter (four beats) a lines and dimeter (two beats) b lines

- The second b line may or may not be repeated

An example from Burns—two wonderful stanzas from “To A Mouse.” Note how the dimeter lines add a certain punch or pithiness to the meaning of the stanza.

But Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best-laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

Still thou are blest, compared wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward, tho’ I cannot see,

I guess an’ fear!

Remember, your poem or six-word essay must have something to do with our trip. It’s not too early to start practicing the limerick, the six-word essay, the haiku, and the Standard Habbie, or to exercise your mind on memorizing a few stanzas!