49 To the Lighthouse

Posted by Christine on May 24, 2015 in Ireland | 5 comments

“England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.” For several hundred years Irish revolutionaries have clung to this equation—sometimes attributed to Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-1798)—as their slogan and as justification for the timing of acts of rebellion. If Wolfe Tone, a leader of Ireland’s Rebellion of 1798, did utter those words, he was referring to the French Revolutionary Wars, the spot of bother on the continent that linked the French Revolution to the Napoleonic Wars in a struggle among European monarchies that lasted a quarter of a century and then some. The rebellion Tone led and died for was intended to catch Britain—always called “England” in the language of Irish independence—at their weakest and most distracted while their army and navy were engaged in the larger struggle. The goal was an independent Ireland backed, surprisingly, by Catholic and Protestant leaders who were tired of living in a neglected and mistreated colony. Like rebellions before it and several after it, the 1798 effort was a miserable failure. But the slogan lived on, and the thinking behind it played a role in inspiring the Easter Rising of 1916 during a very dark time for Britain in World War I. The Rising also failed, but it ignited a series of events that did lead, eventually, to an independent Ireland.

But even an independent Ireland—the Irish Free State formed in 1922—was not yet ready to forgive and forget, and when the rest of the world went to war again in 1939 and after, Ireland remained neutral, wary of siding with their former colonizer even against as threatening an enemy as Nazi Germany. It’s hard to believe that any European country could remain neutral in the circumstances, and the stance is not the noblest moment in Ireland’s history. But centuries of resentment and hatred–the legacy of imperialism–do not recede in a few decades. We now know that during World War II the Irish government did secretly support the Allied cause in several ways, most notably perhaps in the form of a very significant weather report delivered on a very significant date from the Blacksod Lighthouse on the Mullet Peninsula, County Mayo (see photo at top). Since reading about this important historical moment, Ron and I have been wanting to see the place where on June 3, 1944, lighthouse keeper Ted Sweeney issued the weather report that changed the world.

I’m always keen to visit lighthouses. After all, I grew up in a town with a lighthouse, Evanston, Illinois, and swam at Lighthouse Beach almost every day in the summers. In the eighties and nineties, we spent twelve summers on Cape Cod while Ron taught at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, and we lived a half a mile from the elegant Nobska Light overlooking Martha’s Vineyard and Vineyard Sound, which I passed several times a day either running, walking, or driving. There was a shorter way to town, but I wanted to round that curve and see the lighthouse every chance I could get. When I’m traveling somewhere, if there’s a lighthouse in the vicinity, I make sure I go to see it.

This year alone I’ve visited several in Ireland’s stunning collection. I wrote about Poolbeg Light in “9 Water, Water, Everywhere,” and it’s only three miles from where I live; what could be more beautiful than a bright red lighthouse surrounded by blue sea and sky? From the coast of Northern Ireland, you can see the famous upside down West Lighthouse on Rathlin Island—the light is at the bottom of the structure built into the cliff face. And in February we took a long, circuitous drive down to County Waterford and out on a very rural peninsula to see the massive Hook Lighthouse poised where Waterford Harbour meets the Celtic Sea. Built eight hundred years years ago, Hook Light is the oldest operational lighthouse in the world. Across the harbour lies the village of Crook. According to one etymological theory, these landmarks gave an important expression to our language. When Cromwell’s fleet was approaching Ireland in 1650 intent on conquering Waterford, he vowed to capture an important stronghold, Redmond House on the western side of the harbour, “by Hook or by Crook.”

What a lighthouse does—light the way for ships at night and during storms—is a resonant concept fraught with meaning. I’ve borrowed Virginia’s Woolf’s novel title for this piece to hail its metaphorical depth. The lighthouses of the world generally stand in some pretty spectacular places, too: on points of land jutting out in wild seas, on cliffs high above dangerous rocks, or on islands or rock formations in busy and remote corners of the global waterways. I don’t think there’s a single manned lighthouse left in the world, but the romance of the keeper’s dedication and poignant loneliness lingers.

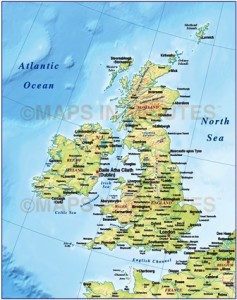

The Mullet Peninsula is not easy to get to. You don’t pass by it on the way to anything else—going there requires a purpose visit and the better part of a day, at least. Located in the extreme WNW corner of Ireland (see red circle on map), the Mullet is nearly an island surrounded by the north Atlantic and Blacksod Bay and accessible by car only at one point. Forty miles from a town of any size, the peninsula is home to fishermen, cattle and sheep farms, and a slew of holiday homes favored by those who really do want to get away from it all. Treeless and open, brilliant green fields amid deep blue on all sides, and ringed with dunes: it’s a bleak and gorgeous place. Once you cross over to the peninsula at the village of Belmullet, you have another twelve miles or so to the lighthouse, located at the southern tip. Add a few miles to that when you find out that the main road has been washed out by a storm—given the size of some of the waves we saw here, that must happen fairly often—and the detours take you right into the pastures with the cows and the sheep.

The Mullet Peninsula is not easy to get to. You don’t pass by it on the way to anything else—going there requires a purpose visit and the better part of a day, at least. Located in the extreme WNW corner of Ireland (see red circle on map), the Mullet is nearly an island surrounded by the north Atlantic and Blacksod Bay and accessible by car only at one point. Forty miles from a town of any size, the peninsula is home to fishermen, cattle and sheep farms, and a slew of holiday homes favored by those who really do want to get away from it all. Treeless and open, brilliant green fields amid deep blue on all sides, and ringed with dunes: it’s a bleak and gorgeous place. Once you cross over to the peninsula at the village of Belmullet, you have another twelve miles or so to the lighthouse, located at the southern tip. Add a few miles to that when you find out that the main road has been washed out by a storm—given the size of some of the waves we saw here, that must happen fairly often—and the detours take you right into the pastures with the cows and the sheep.

It had rained all morning as we drove down from Donegal, but the two hours we spent “on the Mullet” were clear, if grim and gray. Because of the open terrain, we could see the lighthouse from quite a distance, though it is not tall. Blacksod Lighthouse was built on the peninsula’s rocky edge in 1854 of local granite. Not a graceful tower like so many lighthouses around the world, this one is utilitarian in design, short and squat, with a small, white, glassed-in “tower” sitting on top to house the light. A public pier and boat launch and a tiny marina surround the lighthouse, all deserted on the day we visited. All around it, the swells and foam of the gray sea rose and fell.

Though Ireland had declared itself neutral as the war—which the Free State Government insisted on calling The Emergency—began to get underway, an agreement with Britain in place since independence in 1922 insured that weather reports from certain Irish stations would continue to be transmitted despite the change in official relations. This arrangement was never extended to Germany. A look at the map suggests why Britain would be so keen to receive weather  bulletins from the neighboring island: Ireland flanks the center of Britain on the west and is the first stop in the path of the Gulf Stream as well as in the path of prevailing winds from across the Atlantic. As I’ve noticed all this year, the weather that comes to Ireland first moves on to Britain and north central Europe, often changing—usually for the worse—but always making its way in that direction towards the English Channel and the continent. As the plans for the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe began to get under way and the location of what would come to be called Operation Overlord was secretly determined, the importance of receiving regular weather reports from the west coast of Ireland became clear. What better place than Blacksod Light to observe what was coming across the Atlantic?

bulletins from the neighboring island: Ireland flanks the center of Britain on the west and is the first stop in the path of the Gulf Stream as well as in the path of prevailing winds from across the Atlantic. As I’ve noticed all this year, the weather that comes to Ireland first moves on to Britain and north central Europe, often changing—usually for the worse—but always making its way in that direction towards the English Channel and the continent. As the plans for the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe began to get under way and the location of what would come to be called Operation Overlord was secretly determined, the importance of receiving regular weather reports from the west coast of Ireland became clear. What better place than Blacksod Light to observe what was coming across the Atlantic?

Ted Sweeney was a member of the Irish coast guard as well as keeper of Blacksod Light. Part of his job was to deliver a weather report by telephone to Dublin and to London every hour. He had no knowledge of what was being planned for the Channel and the beaches of Normandy when on the morning of June 3, 1944, he issued his hourly forecast: “a Force 6 wind and a rapidly falling barometer.” D-Day was planned for June 5, the timing based on the moon cycle and the tides as well as on military considerations, and if it didn’t take place on the fifth, sixth, or seventh, the Allied forces poised in Britain would have to wait another month. No one wanted to wait; everything was in readiness for the invasion, and the weather might prove to be even worse in July. Later in the day, Sweeney received several telephone calls from Britain asking him to recheck and repeat his forecast.

On the basis of the last of these calls, on June 4th General Dwight D. Eisenhower postponed the D-Day invasion to June 6, which turned out to be a far better day than the fifth for the massive air and sea operation. Thousands of lives and much necessary equipment were saved as a result of the postponement. In spite of its neutrality, Ireland had played an important role in Allied efforts to defeat Germany. Today, a simple plaque on the side of the lighthouse commemorates the event: “D-Day Weather Forecast sent from Blacksod 4th June 1944.”

Visiting places where history happened often helps you understand the people and events better, sometimes raises questions about the stories you’ve been told, and even on occasion offers a new interpretation of what happened. Seeing Blacksod Lighthouse was a far simpler occasion for me. I just wanted to see the place where such a tiny action—a man doing his hourly job to the best of his ability—altered the course of history.

For more information, see “How Blacksod lighthouse changed the course of the Second World War,” Irish Independent, 1 June 2014.

Fascinating and resonant.

just read this to Mike while driving through Wichita Kansas. (No lighthouses here, but lots of grain silos). Mike’s comment: “fascinating.”

I feel as though I’m riding in the backseat of your car as you describe some of these adventures, Christine. I loved this trip! This one prompts me to think about all the other unsung people who were essential in some way to the events of June 6, 1944.

Jim,

You are a great reader and I really appreciate the comments. Thanks for reading!

This, again, is one of these in-depth-researched pieces I like so much in your blog. D-Day indeed changed the world for the better.