51 Woodbrook

Posted by Christine on Jun 10, 2015 in Ireland | 25 comments

Oddly enough, one of the best books about Ireland—a book praised by Seamus Heaney and Brian Moore among others—is a memoir by a Scotsman who lived in County Roscommon for just ten years during the 1930s. Woodbrook by David Thomas was published in 1974 and was instantly recognized as a masterpiece. Many writers and others talk about its influence on them. Des Kenny of the legendary Kennys Bookshop in Galway included it in his book Kenny’s Choice: 101 Irish Books You Must Read (Curragh Press 2009). Though I’m always on the lookout for interesting memoirs, I picked up Woodbrook by accident on a visit years ago to Strokestown House, a Palladian mansion also in Roscommon that today houses a museum dedicated to the Great Famine. The Woodbrook family, the Kirkwoods, and the Strokestown family knew each other, as families from the great estates or “Big Houses,” as the tradition is called in Ireland, were  likely to do. When I eventually got around to reading it one summer, I was immediately entranced, not only by the elegant writing, but also by Thomson’s unusual interweaving of memoir, geography, and local and national history. If you are looking for a book that reads like a dream and evokes the essence of Ireland, you can do no better than to read Woodbrook.

likely to do. When I eventually got around to reading it one summer, I was immediately entranced, not only by the elegant writing, but also by Thomson’s unusual interweaving of memoir, geography, and local and national history. If you are looking for a book that reads like a dream and evokes the essence of Ireland, you can do no better than to read Woodbrook.

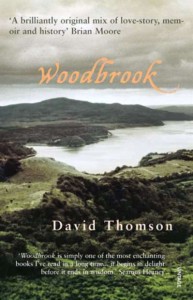

Woodbrook was the name of the house and estate of the Kirkwood family, who hired the eighteen-year-old Thomson as a tutor to their children in 1930s. Located amid the lush plains and quiet lakes of Ireland’s Midlands, the house had been built by the Phibbs family in 1780, possibly on the site of an earlier structure, and the Kirkwoods bought it from them in the 1860s, adding wings on either side of the original square house. Both family were English in origin and arrived in Ireland as a result of “plantations”—land grants designed to populate Ireland with families from the British aristocracy regardless of any native Irish claims. In addition to farming their land, the Kirkwoods bred racehorses and one of theirs, a horse named Woodbrook, won the Grand National in 1881, a glory that the family were never quite able to equal again. By the time Thomson turned up at Woodbrook, Charles and Ivy Kirkwood were trying with little success to keep the place going. By the end of Thomson’s tenure with the family, they had to sell Woodbrook and move to more affordable accommodations in County Wicklow. A large portion of the surrounding land was sold to become the Carrick-on-Shannon Golf Club, so at least it survives today as open land. Amid what’s left of the forest and farmland sloping down to the lake (see photo at top), the house is still standing and still recognizable, though nearly derelict, as are most of the few remaining Big Houses in Ireland.

By now you’ll have guessed that somehow or other I found my way to Woodbrook, and you would be right. I can’t really tell you the details of how I got to walk on the lane leading up to the house that Thomson and the Kirkwoods knew so well, catch at least a glimpse of the house, and take a good long look at the beautiful countryside of pastures, lakes, and forests in which it is set. My adventure may or may not have included breaking and entering (The gate wasn’t actually locked.), impersonating a journalist (I have written articles for newspapers.), trespassing (Oh, there were signs?), mud up to the ankles, an angry farmer, and flight down a country road that dead-ended at a lake. If I did any of this, I would have been aided and abetted by Dave Yeates, who never fails to enter enthusiastically into my plans (“I love your harebrained schemes!”), no matter how unwise. Suffice it to say, the house is not open to the public.

We didn’t get to stroll the grounds of Woodbrook, listening for the echoes of the past, or gazing from the windows or terrace at the lovely countryside sensitively preserved, as you can at Lissadell, Muckross House, Mount Stewart, or Strokestown House, but I’m still glad I went. The book depends so much on the house and grounds that experiencing the setting, taking in the dimensions and angles first hand, feeling the sun on your face and the rain in your hair all help to plumb the depths of the written word. Thomson describes the house, grounds, and surrounding country vividly, weaving in stories from the past and the present to bring Woodbrook alive and give it resonance, not only for himself but also for readers on the far side of the earth who might never have the chance to visit County Roscommon. I wanted to see for myself the place that inspired and incubated such writing; to walk in the footsteps of Thomson, the Kirkwoods, the Maxwells, and all the rest; to kick the rock and thereby prove the existence of Woodbrook.

The Kirkwoods belonged to the class of people called the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, or one or the other of those terms. It would be easy to define them as protestant (Church of Ireland or the Anglican Church) English people who owned land and houses in Ireland and who came over occasionally from their real homes across the Irish Sea to make use of their holdings, but of course it is far more complicated. Some of the ascendancy were Catholic: some of these were descendants of families who came to Ireland in the twelfth century, so they were not exactly recent interlopers. Most were protestant and had ancestors who received land in exchange for services or loyalty from English monarchs starting in the early 1600s during the “plantation” of Ireland. Some considered themselves entirely English and rarely visited the wild island to the west; these “absentee landlords” left their estates in the hands of managers or agents who often ran them for their own gain without regard for the welfare of the tenants, as the Great Famine of 1845-52 would reveal.

Other members of the ascendancy very much considered themselves Irish, or Anglo-Irish, or Irish-English and lived most of the year in Ireland, making an effort in many cases to do well by the people and land under their care. Over the centuries, the Anglo-Irish were to play extremely important roles in Irish history and culture, particularly in the independence movement. Wolfe Tone, Robert Emmet, Thomas Davis, John Mitchell, Charles Stewart Parnell, Douglas Hyde, Roger Casement, Constance Markievicz and many other famous nationalists were all members of this group. And yet there were others among the ascendancy who clung to their Englishness and looked upon their Irish properties and identities as inferior to their British roots. In her novel about Ireland in the early 1920s The Last September, Elizabeth Bowen, a member of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy herself, beautifully portrays the nuances of this identity with all its conflict, guilt, nobility, greed, snobbery, ideals, crimes, culture, and divided loyalties. The loyalties and “Irishness” of the ascendancy are still debated here today, though through intermarriage, emigration, and other means, the categories and the terms of definitions have become even more blurred. Interestingly, some of the Anglo-Irish in Ireland still retain the titles conferred on them by the British monarchy over the centuries—Marquess of Sligo, Earl of Drogheda, Duke of Leinster, etc.—even though the Republic of Ireland does not recognize these titles. It is not difficult to understand why resentment lingers.

My glimpse of Woodbrook; the wings were removed by the time of Thomson’s 1968 visit, and the house was restored to its original size and shape.

For better or for worse, the ascendancy represented British imperialism, and their estates were seen as outposts of colonial power. Because Ireland was a colony and its affairs were managed by people in London who had little interest in or knowledge of what was needed on these remote estates, the system of absentee landlords resulted in exploitation of tenants and general decay of the land, buildings, and other holdings. While Ireland never had as much wealth or anywhere near as many great castles, mansions, or estates as England, Scotland, or Wales, the Big Houses played an important role in social, cultural, and especially literary history. The Big House was seen as a microcosm of the power struggle with Britain, and Big House novels formed the core of Irish fiction up until the early twentieth century. These novels often critiqued the very class which they depicted and from which they sprang. A funny and very pointed short novel that does just this is Castle Rackrent by Maria Edgeworth, published in 1800 and sometimes deemed the first in the genre. In this innovative novel, which was admired by Sir Walter Scott and was one of the first to employ a servant narrator and to portray regional dialects and customs, Edgeworth satirizes not only her own class but all who play a part in the deplorable state of social and economic relationships on the colonial estates of Ireland.

The ascendancy world that Edgeworth satirized was already beginning to come undone when she published her novel and would be finished off by the land reform movement in the ensuing hundred years. From the 1880s to the early 1900s, a vigorous Irish-led movement to persuade the British government to transfer ownership of estate property from ascendancy landlords to the farming families who had worked the land for centuries gained traction, and ownership of Irish land began to change. Along with the transfer of property to tenants under the Land Commission, the social order in Ireland also underwent a dramatic transformation. Some ascendancy families started to pull out, selling their houses and remaining land and returning to Britain. The War of Independence (1919-1922) and the Civil War (1922-23) caused some Anglo-Irishfamilies to feel even more unwelcome, and many of them saw their houses burned down by rebel raiding parties, who were sometimes targeting oppressive landlordsand other times simply expressing their newfound power. The houses that weren’t destroyed fell into ruin. This was the fate of two Big Houses that were important to literature: Coole Park, where Lady Augusta Gregory had entertained and supported W. B. Yeats and other writers; and Elizabeth Bowen’s estate, Bowen Court, one model for the house in The Last September. The families who had owned the houses no longer had the money to keep them up, and the fledgling Irish Free State had no money and no interest in preserving what they saw as monuments to eight hundred years of British rule. The era of the Big House had come to a close.

This was the state of things in Ireland when David Thomson came to work for the Kirkwoods. He was almost perfectly situated to portray the last days of the ascendancy and the shifts in the social order that marked this period. He was an outsider of another kind, a Scotsman who had been born in India and was studying at Oxford, working for an Anglo-Irish family and living in Ireland for much of the formative time between eighteen and thirty. His years with the Kirkwoods living in the verdant pastures of central Ireland opened his eyes to many things and started him on a path to becoming a writer. As the children’s tutor, he was in social limbo at Woodbrook, not really a servant, but not completely of the family and their associates either. For Thomson the future writer, this turned out to be an advantage, as he was able to move freely in both words, learning the stories and ways of the estate from farmhands and servants as well as from the ascendancy class. And because it was Ireland, not England, the countryside not the city, social class was far more fluid. When the Kirkwoods threw their annual birthday party for the young Phoebe, everyone associated with the estate was invited, mingling freely without the more formal strictures that might have held sway in Dublin, an English country estate, or London.

What makes Woodbrook remarkable is not the portrayal of a family and a Big House in decline—that was happening all over Ireland and was the focus of many literary efforts—nor the coming of age story or the love story with its sad ending, but rather Thomson’s thoughtful, evocative writing and his innovative blending of subject matter. In this work, Thomson reimagined autobiography, using his personal story as the framework for exploring local and national history and recording the natural history of the surrounding area. In weaving together these various strands to create a whole narrative that is both historically grounded and emotionally compelling, he was one of the inventors of what is today called “creative nonfiction,” a genre that depends on careful observation, human interest, and research but that also recognizes and embraces the story of “I” and its relevance to layered contexts. In my first reading of Woodbrook and even in my second and third, I came upon insights about Irish history and other subjects that I’ve encountered nowhere else. In Thomson’s hands, the weaving together of subject matters once thought to be incompatible achieves writing of great beauty and great truth.

I don’t want to spoil any more of the story of Woodbrook by talking about what happens; it’s a book that has to be experienced, not summarized or even analyzed. It has been a model for me in my thinking and writing about Ireland, as well as in my wanderings around the countryside and encounters with places that have inspired the writings of others. If you love writing about place or writing about Ireland, I urge you to read Woodbrook. I have three or four copies I can lend out.

Thomson ends his memoir with the story of his last visit to Woodbrook in 1968 long after the Kirkwoods had sold off and moved away. From his description of the sad state of the house and land, things have not changed much between his visit and mine. From the glimpse I caught of the house, it was still in very bad repair. The great trees that had framed it on the hill above the lake had all come down from age or storms, though smaller trees and shrubs now shelter it from would-be pilgrims on the roads and paths surrounding the estate. Though much of the original land belonging to the estate was sold off, the setting is still utterly rural, and the lushness of the pastures, the blue calm of the lake at the foot of the hill where the house stands, and the leafy lanes trailing around its edges are very much as they would have been when the Kirkwoods and Thomson spent their summers at Woodbrook.

Reflecting on the political situation particularly in Northern Ireland at the time of this return visit, Thomson ends his story with an insightful passage that illustrates the importance of Woodbrook and shows why studying the rise and fall of the ascendancy and the Big House is so essential to understanding Ireland, north and south. After describing the decayed state of Woodbrook and listing the other great houses in the area that he had frequented with the Kirkwoods and that were destroyed, torn down, or left to ruin, Thomson writes,

. . .the last vestiges of the Anglo-Irish landlord system had passed away.

Those remnants of colonial rule, such as the Land Commission, which touched on practical affairs were all beneficial so far as I know, but because I re-visited Ireland in 1968, the year in which the traditional ‘troubles’ were resumed—in the Six Counties [Northern Ireland] this time—I was more conscious of the evils that remain outside the Republic. The situation in the north-east remains the old one—the segregation, the inability of natives and settlers to live together as one society, the settlers’ fear and their determination to hold exclusive power. This is now the cause of violence as it was in 1798.

It is as though the whole of Anglo-Irish history has been boiled down and its dregs thrown out, leavening their poisonous concentrates on these six counties (323).

David Thomson. Woodbrook.(1974) London: Vintage, 1991.

Fascinating piece; just ordered the book.

The book is on my list. As is Ireland.

Lee, look for notice of alumnae trip we are planning for June 2016. An email about it should be going out soon. Thanks for reading!

My mother’s side is the Kirkwood of woodbrook my g grandmother is Isabela matilda emily Kirkwood married John Law Hackett of Ardcarn house in 1869 !

Wow that is interesting! I subsequently visited Phoebe Kirkwood’s grave in Enniskerry. It was very hard to find because there is no longer a marker. It’s sad that traces of the book are no longer visible to the public!

Hi Christine, have been trying to find it for a while. We named our daughter Phoebe – from the book – and now live near Enniskerry. Have been round and round the churchyard. Any tips ?

Dear Harriet,

We use a chart of the graveyard that was in the church foyer adjacent to the graveyard. We found her grave and then noted the names of the two graves on either side–good thing, because when went out to see it, there was no headstone on hers, just a space between the other two. I hope this helps you! If that chart is not posted (it looked pretty old) you might ask the reverend or someone at the church where it is.

Good luck!

Christine

Harriet,

I saw your comment about Phoebe Kirkwood. Isn’t it strange that she has no headstone?

Julian Vignoles is my name. I’ve written a biography of Davit Thomson.

Hi Christine, lovely to read this! Patrick, We are related as my Great,Great Grandfather was Andrew of Cloongownagh who was a cousin to Thomas of Woodbrook. I have lots of family information to share together with old pictures. Would be good to get in touch.

Thank you for your kind words. It’s so great to have descendants connected this way!

Hi Stuart and Christine, you can message me threw Facebook Patrick Feland British Columbia or email trucker1968@hotmail.com

thanks for that Christine very well said I read the book many years ago had a profound effect on me being an emigrant from Ireland about a pre war society of

very well said Cristine I read the book quite awhile ago being an emigrant from Ireland had a profound effect on me about a pre-war society anglo irish relations etc also Bowans Court by Elizabeth Bowen is great Thomson also wrote about his native Scotland which was great Nairn in darkness and light

similar to Woodbrook only different countries

thanks for your input which was great yours Matt

i

Thank you for your kind words! This book is very important to me and increases in importance every time I read it. I also love Scotland and will now track down Thomson’s writing on his home, thanks to you. There’s also a very good biography of him. Thanks, Matt!

Thank you, Christine. I came upon David Thomson’s wonderful People of the Sea, then found Nairn in Darkness and Light, and finally the superlative Woodbrook. A Google Earth search for “Woodbrook, County Roscommon” takes one to an abandoned site, and I concluded the Kirkwood house was gone. How grateful I am to be enlightened by this very knowledgeable, entertaining entry. Your historical descriptions, photos, and humorous narrative foster curiosity without giving any plot essentials away. I hope many readers follow your enticing lead to Thomson’s book.

Dear Kerry, Thank you for your kind words. Everyone to whom I’ve recommended Woodbrook has loved it. I’m glad to find another kindred spirit. By the way, After this post I went to find Phoebe’s grave in Enniskerry. Using the cemetery map in the church, we found it after much searching, but it was unmarked (we identified it by the graves next to it). I hope some family member eventually decides to fix it up. Thanks again, Christine

I have in my hand at the moment a letter written and signed by James M. Kirkwood, “of Woodbrook Lodge” dated February 9, 1848. He writes of the dire need of clothing for children in his area and writes to the Quaker Society of Friends in Dublin for help. “The very bags you sent… were converted into clothes. Several of who received your clothes this week had no other covering.”

This was in general a very poor area as I understand it. Thanks!

My grandfather spoke of dinner at Woodbrook. Born 1897 Sinclair Torton Kirkwood, had a brother Henry and a sister – I can’tell recall her name . . .

I try to put a old picture on site me thinking it’s James Kirkwood my Facebook is Patrick Feland my Mother is Patricia feland Hackett , i have one picture im thinking our gg uncle James Kirkwood of Woodbrook!

Christine thank you for your beautiful article about visiting Woodbrook. It’s funny how Woodbrook lingers in the hearts of so many. I’m the granddaughter of William Maxwell of the Maxwell brothers written about in David Thomson’s book. We have grown up with the stories of Woodbrook but I have never set eyes on the house. Did you know that not so many years later the Maxwells bought Woodbrook? Michael Maxwell came home from America with money and bought Woodbrook – the stuff of dreams. He left it in the care of his brothers, who farmed it until eventually they could no longer afford the crippling rates applied by the government of the day and it went out of their possession and into those of the current owners. It’s a sad epilogue, but Woodbrook continues to fascinate us all to this very day.

Thank you for writing! I am haunted by this book, as so many are. My glimpse at the house wsa probably not strictly legal, but I’m glad to know it still stands!

Please contact

In 2006 my wife, Carol, and I traveled from Boston to Shannon Airport and up along the Shannon River to Carrick-on-Shannon to visit with family recently identified in Derreenargon and at the “Woodbrook Estate”. John A. Malone and his wife, Mae, were our gracious hosts for dinner in Carrick-on-Shannon and a visit to “Woodbrook”, their home. We talked about family and raising Angus cattle, their specialty, late into the evening, warmed by a peat fire, This was the latter part of May and they were concerned that by the wet condition of the lands for the cattle. We were thankful that family in Massachusetts helped us to contact and visit with such caring folk. We retain a fine memory of the visit to “Woodbrook”.

What happened to Phoebe’s sister?

I have tried to get ahold of her daughter Jessica and no response yet, Jessica Phibbs!