For poetry and other materials related to Derry, see “Trip Documents” or click here.

You might be wondering why the name of the city we will be visiting in Northern Ireland is often represented two ways. The story behind that practice says a lot about the city’s history. “Derry” is the city’s original name; it comes from an Irish word “doire” (DOY-ruh) meaning “oak grove.” St. Columcille (also Columba, Columb), one of Ireland’s “top three” saints along with Patrick and Bridget, established a monastery on the site in the sixth century. Columcille had a great fondness for his homeland: long after he had moved to Scotland to found the famous monastery at Iona, he wrote poetry full of longing for Derry:

It is for this I love Derry,

For its quietness, for its purity,

And for its crowds of white angels

From one end to another.

A scholar, monk, and warrior, St. Columcille had a fascinating life and was involved in what is considered to be the first copyright case, the “Battle of the Book” (he lost). The Church of Ireland (Episcopal) cathedral in Derry is named after him (St. Columb’s). Remember that the oldest and most beautiful churches throughout Ireland—including the magnificent St. Patrick’s in Dublin—are Church of Ireland properties rather than Catholic. When Henry VIII decided to dissolve the monasteries in his kingdom in order to destroy their power and grab their wealth c.1540, he absorbed these edifices into his new church. And that was the root of the “Troubles” in Ireland for centuries to come. Under subsequent protestant monarchs, Ireland was “planted” with settlers to spread the faith and the king’s sovereignty. The Catholic, Gaelic speaking residents and landowners (or so they thought) of Ireland were not consulted, and many lost everything to the colonists. Ulster, the northern quarter of Ireland and the closest in proximity to the other island, was the most heavily settled during this time. The “plantation of Ulster” in the early seventeenth century made protestants wealthy landowners and Catholics poor tenants or worse, setting the stage for the sectarian strife of the twentieth century.

Derry was not destined to be a place of “quietness” for long. Strategically located on the River Foyle connected to a large inland sea called “Lough Foyle,” the settlement grew quickly during the plantation period, and in 1613 was granted a royal charter by King James I. London-based guilds gave money to build the walled city, and their contribution would be commemorated both in the city’s new official name, Londonderry, and in its most famous building, the Guildhall, built in 1890 and today the seat of the city government.

Derry was not destined to be a place of “quietness” for long. Strategically located on the River Foyle connected to a large inland sea called “Lough Foyle,” the settlement grew quickly during the plantation period, and in 1613 was granted a royal charter by King James I. London-based guilds gave money to build the walled city, and their contribution would be commemorated both in the city’s new official name, Londonderry, and in its most famous building, the Guildhall, built in 1890 and today the seat of the city government.

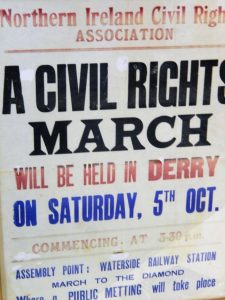

At the behest of Ulster protestants who wanted no part of an independent Ireland and in order to shore up votes for the political party in power, Britain partitioned Ireland in 1920, creating the six-county province of “Northern Ireland” (the remaining twenty-six counties would become the Irish Free Sate in 1922 and the Republic of Ireland in 1949). The six counties were chosen because they had a protestant majority. While religious differences between the two sides were minimal and not part of their conflict, class differences deepened and led to Catholics being excluded from access to housing, jobs, voting rights, and more. No wonder their acts of defiance soon began to resemble those of the American Civil Rights movement.

During the most intense era of sectarian strife, The Troubles from 1969-1998, the name Londonderry became controversial, with Catholic nationalists and republicans adhering to the original “Derry” and protestant unionists and loyalists standing by “Londonderry.” During the peace negotiations in the 1990s brokered by President Bill Clinton and Senator George Mitchell, the president came to speak in the city. Clinton and Mitchell are still praised all over Ireland for their fairness to both sides of the conflict, and the people of Derry were anxious to see how Clinton would handle the name controversy. Ever the diplomat, he spoke of the “city of Derry. . .in the county of Londonderry,” using both names throughout his stay.

Derry city center was nearly leveled during The Troubles and was the site of much bloodshed and destruction, including the infamous “Bloody Sunday” massacre of 30 January 1972. The city has come a long way since the Belfast or Good Friday Peace Agreement of 1998 and is now a center for power sharing, reconciliation, and planning for a peaceful future. But the city name is still a problem for some. Outside Derry you’ll notice road signs where the “London” of the official name “Londonderry” is crossed out. When conferences are held there, the organizers must produce two sets of name tags, one saying “Derry” and one saying “Londonderry.” While most attendees don’t care what their name tags say, some will ostentatiously rip up and toss out the one they don’t like. Though a law in 2007 declared “Londonderry” the official name, today most people from both communities call the city “Derry” for the simple reason that it’s shorter and easier to say.

You may also hear Derry called “Stroke City,” a name conjured up by  a local radio personality to reflect the stroke mark (technically a “virgule”) often seen between the two names, as in “Derry/Londonderry.” Others believe “stroke” refers to the life-threatening medical condition possibly induced by the city’s history of violent conflict or Northern Ireland’s predilection for large platefuls of fried food.

a local radio personality to reflect the stroke mark (technically a “virgule”) often seen between the two names, as in “Derry/Londonderry.” Others believe “stroke” refers to the life-threatening medical condition possibly induced by the city’s history of violent conflict or Northern Ireland’s predilection for large platefuls of fried food.

Derry is Northern Ireland’s second largest city after Belfast and is today a beautiful and fascinating place. An intact wall built in the early seventeenth century rings the city center, affording marvelous views of the old city inside the wall, the River Foyle with its elegant bridges, and the surrounding scenery. The Guildhall, St. Columb’s, the Craft Village, and the Tower Museum chronicling the city’s history are the must-sees within the wall.

Our visit will include a guided wall walk; a look at some of the famous political murals that commemorate the conflict ; the Guildhall; and the Museum of Free Derry, an interpretative center dedicated to the story of Bloody Sunday and staffed by relatives of the fourteen peaceful protesters who were killed by the British army on that day.

Whenever I’m in Derry/Londonderry, I make it a point to walk across the stunning Peace Bridge, a foot and cycling bridge opened in 2011 to symbolically join the largely nationalist “Cityside” and largely unionist “Waterside” communities (see slideshow below). On the day the bridge opened, thousands of people on both sides of the river thronged the streets, lining up to walk across the bridge, many of them in tears. Today, the bridge is the site of festivals, performances, and other joyful activities. (see video). Visitors wonder why the Peace Bridge forms an “ess” curve instead of reaching directly across the River Foyle as the other bridges do. The answer is simple: the path to peace is never straight.