13 Folding Landscapes

Posted by Christine on Oct 2, 2014 in Ireland | 6 comments

Rummaging through boxes in my parents’ attic one day back in the seventies—hoping to find items to fill up my new apartment—I came upon a pink-flowered china coffee server, a pitcher of sorts, lidless and dusty, that had once belonged to my mother’s parents. It wasn’t valuable or useful, but it was kind of pretty, and I remembered seeing it on the mantle in my grandparents’ tiny house when I was five or six. I took it with me and kept it for years in a china cabinet with other bits and pieces from the attic and from flea markets I visited over the years.

One day in the spring of 2000, some twenty-five years later, my brothers and I and our families were cleaning out my parents’ house prior to selling it. It was a tough day for us. I sequestered myself in the attic where I could cry secretly and where most of the packing up had already been done. As I drifted around the dark, musty room, something on the window sill caught my eye. There was the lid of the china coffee server—the unmistakable pattern and shape telling me instantly what it was. Why was it on the window sill? Why hadn’t it been packed or thrown away years ago? How had I missed it a quarter of a century earlier? What made me look at the window? Finding it somehow made me feel better, took the edge off that difficult day. Back in Atlanta a few days later, I reunited lid and pitcher, the lid settling perfectly into place with a soft clink.

Sometimes the stars align, and a few pieces of life’s chaotic jigsaw puzzle come together unexpectedly; for a moment, you can almost imagine the picture you’re working to assemble.

I had another of these moments a few weeks ago on a cloudy Friday afternoon in Roundstone, Co. Galway, a small village perched on a bay. Ron, our friends from California Mark and Maureen, and I were spending a long weekend exploring the western part of Connemara, and our B&B host from the night before in Spiddal had urged us to visit Roundstone on the drive to Clifden, saying it was a “lovely place.” And indeed it was, even on that gray day. Brightly painted houses and shops lined the one main street curving up a small hill above a tiny harbor, all within view of the sharp peaks of the Twelve Bens to the north, though the mountains were just a bluish outline in the mist.

Ron had led us all down to the quay, and I was looking at the boats and taking pictures of the harbor when Mark came up to me with some kind of brochure in hand. “There’s a lecture going on right now in that building,” he said, pointing to a white house on the water’s edge. “You might be interested…the artist’s name is Tim Robinson.”

Ron had led us all down to the quay, and I was looking at the boats and taking pictures of the harbor when Mark came up to me with some kind of brochure in hand. “There’s a lecture going on right now in that building,” he said, pointing to a white house on the water’s edge. “You might be interested…the artist’s name is Tim Robinson.”

I stopped in my tracks. “Tim—Robinson?” I said faintly. “The Tim Robinson?” Mark smiled. He didn’t know what I was talking about, but he handed me the brochure, and I read the blurb he was pointing to. Yes, it was the Tim Robinson. “I’ve read all his books!” I said, my voice suddenly tremulous. Tim Robinson, one of the greatest of all contemporary nonfiction writers, surely the greatest writer on the subject of the Irish landscape. His books on the Aran Islands, the Burren, and Connemara had shaped my thinking about Ireland and about writing for years. Tim Robinson—the only writer I mention in my sabbatical proposal, the only writer I mention in the “About the Author” section of this blog.

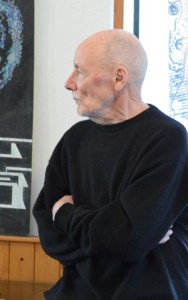

Walking quickly over to the house, I slipped into the crowd filling the two rooms and spilling out the doorways. There, leaning against a table and talking in quiet voice with a slight English accent (he’s from Yorkshire), was the great Tim Robinson, a tall, spare, nautical looking man in his seventies. By this time Maureen had made her way into the house and beckoned to me to stand near her where the view was better. There in the back of the room, I stood very still, trying to catch every word, but my mind was racing. “This is Tim Robinson!”

I should mention that the date was September 19, “Culture Night” throughout Ireland, when writers, artists, musicians, performers, and institutions open their doors to the public for a celebration of the arts. The events get started during the day in some places, and later we saw signs around the village announcing this one. The Culture Night brochure called it a “pop-up gallery”: “Folding Landscapes: An exhibition of paintings by Tim Robinson with a talk by the artist. A rare opportunity to see paintings made by the renowned writer, artist and cartographer….”

The white house on the water is actually Robinson’s studio and the home of the company he and his wife set up called “Folding Landscapes, “a specialist publishing house and information resource centre dealing with three areas of particular interest and beauty around Galway Bay: the Aran Islands, the Burren and Connemara” with the purpose of publishing “Tim Robinson’s maps and some of his books.” The phrase “Folding Landscapes” captures the nature of maps and encompasses the books as well, with their rich and detailed analysis of the physical landscapes and the histories that attach to them. But it also refers to the rocky, layered landscapes of this part of the world, like the Cliffs of Moher, the jagged cheval de frise at Dún Aonghasaon on Inishmor, or the pleated folds of the Burren in the photograph at the top of this page.

I didn’t know any of that at the time. It was enough to hear him talk about his work, about the paintings he had made years earlier as part of his landscape study, about taking his works to be archived at the National University of Ireland at Galway just before the studio was flooded, about a shift in his later work to include more imaginative writing. And then he did a short reading from his 2002 book Tales and Imaginings. I couldn’t believe my luck—I was hearing Tim Robinson talk and read.

After the reading, the organizer thanked him and announced the next events of the afternoon. People started to leave the studio. Though I wasn’t sure I would make any sense, I resolved to wait for an opening, introduce myself, and thank him. In a strangled voice (you know me, I was trying not to cry), I did just that, or at least I think so. I was not very coherent. He was very gracious and talked to me for a few minutes about the new book and the terrifying but liberating (his words) move he had made in his writing. We shook hands. While he talked to a few other people, I went to the back of the room where I could unobtrusively take a picture—I think I got him just right.

I was going to try to convey the essence of Tim Robinsons’s writing about landscape, but I’ll give you a sample of it instead. You have to immerse yourself in a whole essay or a whole book to understand his particular brand of mathematical exactitude of description coupled with imaginative envisioning of the stories connected to places. This excerpt is the last paragraph of Connemara: A Little Gaelic Kingdom.

Seánin also showed me a dyke or blackish rock cutting westwards through the blond granite of the shore, which he said was the way a saint took to Mac Dara’s holy island, according to the seanchas, the old lore passed down by the seandream, the old folk. (Of all the words in the Irish language the most potent are sean, old, and siar, westwards or backwards in time and space. Some might say they are the two great bugbears of the nation, but I have written this book to celebrate their unquenched energy and mutual intrication.) We talked of the offshore rocks, too. Nearby was the Bruiser Rock, which was discovered the hard way by the Bruiser, a British gunboat, when distributing food around the famished islands in the 1880s. Further out I could see dozens of others, each of which, I knew, would be the anchor stone for a web of stories set, most of them, in the half-dimension of things not to be believed in but to be wondered at. Tokens of the inexhaustible fractality of both the real and the imaginary, they challenged the art of words. Every tale entails the tale of its own making, generalities breed exceptions as soon they are stated, and all footnotes call for footnoting, to the end of the world. So, discourse being fractal and life brief, I will let the saint’s black shortcut lead me between those rocks and over the waves to his island, from which it is no distance at all to my own home.

In being so starstruck—a babbling teenaged fan in the presence of Mick Jagger—I surprised myself. We have a writers’ festival at Agnes Scott, and through that I’ve hobnobbed with the likes of John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, Anita Desai, Junot Diaz, Rita Dove, Joy Harjo, more well-known Irish writers like Eavan Boland and Paul Muldoon, and many, many others. No problem. Maybe it was the unexpected nature of my encounter with Tim Robinson, or seeing him in the landscape he has written so eloquently about, or meeting him when I’m in the middle of my own project writing about Ireland’s landscape.

I know I’ll never forget that chance meeting—the “anchor stone,” I hope, for a “web of stories.”

Selected Works by Tim Robinson

Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage, 1986 (This is a good place to start if you want to read some Tim Robinson.)

Stones of Aran: Labyrinth, 1995

Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara and Other Writings, 1996

My Time in Space, 2001

Tales and Imaginings 2002

Connemara: Listening to the Wind, 2007

Connemara: The Last Pool of Darkness, 2008

Connemara: A Little Gaelic Kingdom, 2011

Connemara and Elsewhere, 2014(See Tim Robinson’s Folding Landscapes web site for information on these books and on his maps, pamphlets, and broadsides.)

Oh, this is wonderful on so many levels. Do you think it matters which of his books to start with?

Robin, I think The Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage would be the way to go. Then you’ll have to go there! Thanks for all of your comments.

What a wonderful, serendipitous encounter! And the paragraph you quote is enough to get me to the bookstore… I love that the “web of stories” lives on the page but is also a physical, mappable thing.

Thank you for this beautiful story. So personal,encapsualting the universal “click of the lid”.

Thanks for your kind words. This encounter meant so much to me!

What a wonderful gift, Christine. Thank you. I have shared another of your posts, this time with my son and his wife, a geologist and mathematician. I have also sent them one of Tim Robinson’s books, The Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage, which you recommended above. Of course I will read it, too.