21 Remembrance

Posted by Christine on Nov 10, 2014 in Ireland | 1 comment

Ninety-six years ago at the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of the eleventh month, World War I formerly ended, a day universally known as “Armistice Day” but often called “Remembrance Day” or “Poppy Day” in Ireland and the UK and “Veteran’s Day” in the US.” For the Republic of Ireland, though, a new consciousness of the role the Irish played in the “war to end all wars” has emerged in the last few years, and like everything having to do with history and remembrance here, it is fraught with complexity and tortured political and cultural meaning.

Ninety-six years ago at the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of the eleventh month, World War I formerly ended, a day universally known as “Armistice Day” but often called “Remembrance Day” or “Poppy Day” in Ireland and the UK and “Veteran’s Day” in the US.” For the Republic of Ireland, though, a new consciousness of the role the Irish played in the “war to end all wars” has emerged in the last few years, and like everything having to do with history and remembrance here, it is fraught with complexity and tortured political and cultural meaning.

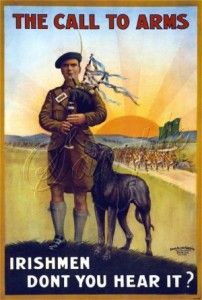

In 1916, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Britain was at war with Germany and the Central Powers. Trench warfare was devastating the British army, and the need for soldiers was insatiable. Member of Parliament John Redmond and his Irish Parliamentary Party urged the Irish to join up, arguing that the British promise of Home Rule for Ireland would be fulfilled upon defeat of the enemy in a war that promised to secure “the freedom of small nations” like “poor little Catholic Belgium,” with whom Ireland identified. Committed nationalists like the young poet Francis  Ledwidge (1887-1917) believed Redmond, seeing their service to the Crown as earning Irish independence after the war. A recruitment campaign aimed at the Irish used religion, stereotypes, and guilt to convince them to enlist. Over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British armed forces, with approximately 30,000 dying in battle, another 19,000 when emigrants were included. Ulstermen were heavily represented in these figures: the north was more British, more protestant than the south then and now. In Northern Ireland there is even an entire museum dedicated to the Battle of the Somme, where many Ulstermen died.

Ledwidge (1887-1917) believed Redmond, seeing their service to the Crown as earning Irish independence after the war. A recruitment campaign aimed at the Irish used religion, stereotypes, and guilt to convince them to enlist. Over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British armed forces, with approximately 30,000 dying in battle, another 19,000 when emigrants were included. Ulstermen were heavily represented in these figures: the north was more British, more protestant than the south then and now. In Northern Ireland there is even an entire museum dedicated to the Battle of the Somme, where many Ulstermen died.

But at that time, strongly nationalist Irish people believed in the slogan “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity,” arguing against participating in the war and sometimes publicly shaming those who did. A banner was hung across Liberty Hall, a trade union stronghold in Dublin, that read “We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser But Ireland.” The war was deeply divisive, never more so than when the Easter Rising erupted in 1916, amid terrible casualties and losses abroad. Irish public opinion sided with Britain at first following the failed insurrection, but the summary trials and executions of fifteen of its leaders within three weeks of the event turned the tide against the British and laid the groundwork for the independence struggle that would culminate in the Irish Free State in 1922, followed by Republic status for the twenty-six counties in 1949. Commemorating the war and its dead has been important in Northern Ireland for a hundred years but ignored or highly controversial in the Republic, another enduring cause of tension between the two sides.

The broader context for the current shift in attitude towards Irish participation in WWI is that Ireland is in the third year of a “Decade of Centenaries,” a period of commemorating important events in the nation’s history, such as the Dublin Lockout of September 1913 (a failed but pivotal six-month strike by thousands of workers in the capital), the Easter Rising of 1916, and various dates from the War of Independence (1919-21). Recognition of these centenaries includes the inevitable unveiling of plaques and memorials; the publication of many books analyzing the events, some using documents only recently made available; art exhibitions, cultural events, parades, and other public celebrations; lively debates about “what might have happened if…” in the op-ed pages of the newspapers; and lectures, conferences, ceremonies, and performances of all kinds.

As an outsider observing life in Ireland for thirty years or more, I’ve noticed a far more open response to such commemorations than I encountered before: a resistance to easy or pat answers coupled with a much greater willingness, even eagerness, to hear and acknowledge contrasting views and to understand figures and events as complex, nuanced—to see them “warts and all.” For example, I’m taking an adult education course taught by professor from University College Dublin called “Uncovering 1916,” and that’s exactly what he’s doing, pulling away the veil of patriotism and nostalgia and telling the story based on the research, analysis, and debate of recent years. The other students in the class—all Irish, most with grandparents or other relatives who witnessed or participated in the Rising—are eager to learn about the events that Yeats famously summed up in the phrase “A terrible beauty is born” in the cold light of analysis, as their probing questions and discussions reveal.

BBC photo of the Glasnevin unveiling on 31 July 2014 to commemorate 100 years since the Great War began

What is remarkable for me and I think for many Irish people is that Ireland’s participation in World War I is, for the most part, meeting this same hunger for knowledge and willingness to accept a far more complex view of the past than has been politically correct before. The Great War has been included in the Decade of Centenaries to an extent unimaginable in the past, when many people here considered joining the British Army to fight the Germans as reprehensible, a sign of allegiance to the oppressor. Today there is much more willingness to consider the complex motives of the men who joined up, including their hopes that Britain would grant Home Rule after the loyal Irish helped them win the war and the importance to many poor families during that time of a soldier’s steady income. True, when the new memorial to the Irish who died in the war was unveiled at Glasnevin Cemetery on July 31 this year before a large crowd with the Duke of Kent as well as other dignitaries present, a few extremist Republican hecklers stood at the gates throwing things and calling out. But no one missed the significance of a member of the British royal family participating in such an event, and many Irish people noted that it was “about time” for those dead to be honored with a monument in such a public place.

The centenary celebrations marking purely Irish events are interspersed with many that commemorate World War I. This fall the Second Annual Dublin Festival of History—an extremely popular public event that is in itself an indicator of a revived public interest in taking a fresh look at the past—focused on the Great War, drawing large crowds to hear Ireland’s role in the war examined and debated. Dublin’s two main theatres, the Abbey and the Gate, along with other venues have launched war related productions this year, including revivals and new work. The magazine History Ireland is sponsoring several “hedge schools” (a centuries old practice in Ireland of educating the community in rural areas through oral instruction often in farm buildings or hedges) around the country on the subject. I went to one where scholars discussed the role of women in the war, and I plan to attend another in a few weeks on the role of Dubliners in the war. In countless other ways, the Great War and Ireland’s role in it are being commemorated but also examined, questioned, and aired.

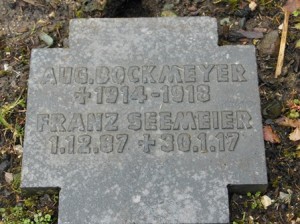

At Glencree Cemetery in the Wicklow Mountains, remembrance extends to 134 German soldiers and civilians from both world wars who died in Ireland.

Both the recognition and the openness to debate are vital to a society that strives to be inclusive and to move positively forward from its past. Here there’s also a powerful practical reason for changing attitudes towards the war. Pride of service and sacrifice in the Great War has long been a cornerstone of Northern Ireland’s national identity. Broadening acceptance and understanding of that history in the Republic is essential to reconciliation between north and south.

In light of the recent violence around Civil War monuments, this post resonates so strongly for me here in Mississippi – highlighting the lack of willingness to move beyond slogans and stereotypes, the lack of a hunger for knowledge, and not just in the South.