29 The Terrible Beauty of Patrick Pearse

Posted by Christine on Jan 5, 2015 in Ireland | 4 comments

Anyone visiting Ireland during the next two years is likely to encounter the young man depicted in the sculpture above, Patrick Henry Pearse (1879-1916)—a national icon and for some, almost a saint.

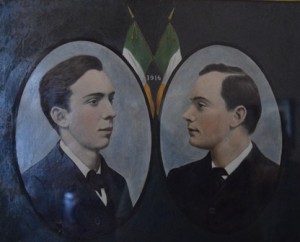

Pearse, along with his younger brother Willie, was one of the “Sixteen Dead Men” eulogized by William Butler Yeats who were executed by the British under martial law following the Easter Rising in 1916. The Rising itself was judged a failure, but the executions of the sixteen leaders—poets, schoolteachers, shopkeepers, and a human rights leader among them—contributed to the transformation of public opinion about the possibility of finally achieving independence from Britain. Pearse was one of the insurrection’s leaders; Willie came along to support his brother but had no role in planning or carrying out the events of the week. His execution surprised everyone, including Patrick, who wrote in his last letter to his mother from prison that he thought that Willie was “not now in any danger.”

Within six years of the executions, independence–or at least some measure of it– was achieved. Today, the Easter Rising is regarded as the seminal event in modern Irish history. Plans for the centenary commemoration in 2016 are already well under way—and already controversial, as have been past commemorations.

Patrick Pearse’s image is everywhere in Ireland—on medals, on portraits in official buildings, on stamps and souvenirs. Even today, no schoolchild fails to learn his name or to connect him with heroism and the long struggle for independence. Yet for someone whose name is a household word, often spoken in hushed tones as his sacrifice is remembered and invoked, he is an enigmatic figure, both inspiring and troubling, someone whose motivations and ethos we may never fully understand.

I encounter Patrick Pearse daily. I walk into town on Pearse Street (formerly Great Brunswick Street) past his birthplace and childhood home, which was also his father’s stonemasonry business, past Pearse Hardware, the Pearse Brasserie, Pearse Gardens, the Pearse Tavern, the Pearse Hotel, Pearse Square, Pearse Station—you get the idea. Hardly a week goes by that I don’t hear someone mentioning Pearse’s name or arguing about the significance of his actions. Letters to the editor in the newspapers debate the merits of the Rising and the role of Pearse and others in promoting “physical force nationalism” in Irish politics, a legacy that haunted the island during the Troubles and lingers even today, when relative peace reigns in both north and south. Many Irishmen grew up like Frank McCourt with the question “Would you die for Ireland?” a reference to Pearse and others, darkening their childhoods.

Though few records survive from Pearse’s last months, there’s no doubt that he was prepared to die for Ireland, perhaps even longing for such an end. I teach a little poem of his in my Irish literature course that sums up in sixteen words many things about his personality and his dreams for Ireland:

Christmas 1915

Oh King that was born

To set bondsmen free

In the coming battle

Help the Gael!

Already planning the Rising at this point, he saw Ireland’s independence as a religious cause resembling the founding of Christianity and, more than once in his writings, likened his own possible death in battle or by execution to that of Christ, a sacrifice that would bring freedom to his people, the Irish. At the end, he even argued that if the other leaders could be spared, his death should be enough to satisfy the British–no doubt he also meant enough to inspire the next stage of the rebellion.

I’ve tried to get closer to Pearse this year, reading about him, walking the streets where he walked in this neighborhood, visiting the places where he lived and worked, studying his poetry and other writings.* There are three places in Ireland where he is most poignantly remembered, two in Dublin and one in County Galway.

St. Enda’s School

Pearse trained in the law but worked primarily as a writer and editor and schoolteacher. He became interested in politics through the Gaelic language and the “Irish Ireland” movement and was for a long time an advocate for Home Rule, or independence achieved through parliamentary means. To inculcate these values in future generations of Irishmen, in 1908 Pearse founded the innovative school for boys, St. Enda’s. In 1910 St. Enda’s moved to an elegant Georgian house in Rathfarnham, a Dublin suburb. The school closed in 1935, but Pearse’s mother and sisters lived for many years in the building, preserving the legacy of the school and of the brothers, Patrick and Willie. Today the Pearse Museum occupies this space.

Visiting St. Enda’s and learning about the school firsthand shed new light on Pearse for me. His ideas for education were innovative and exciting. When others were advocating Gaelic only education, he stressed the importance of both Irish and English for the insipient nation, making his school firmly bilingual. Unlike most schools of his day, at St. Enda’s the arts, including drama, played an important part in the students’ daily lives, as did physical exercise and hands-on scientific exploration. William Butler Yeats and other important writers and artists of the day lectured at the school, and today you can still see the stage where they stood to address the pupils.

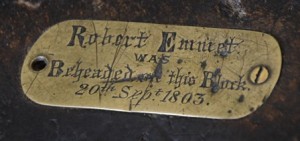

St. Enda’s has been beautifully restored and, because it remained in the family for so long, holds many Pearse family furnishings and personal items. You can browse Pearse’s books along with the patriotic artworks and memorabilia he collected. Pearse was fascinated by the words and exploits of Irish patriots who had gone before him. He was particularly enthralled by Robert Emmet, whose short, failed rebellion against British rule in 1803 ended with his execution by hanging followed by beheading. Pearse owned a death mask of his hero and the block on which Emmet was said to have been beheaded—grim items for a school to display and stark reminders of the depth of Pearse’s commitment to the “die for Ireland” ideal.

St. Enda’s has been beautifully restored and, because it remained in the family for so long, holds many Pearse family furnishings and personal items. You can browse Pearse’s books along with the patriotic artworks and memorabilia he collected. Pearse was fascinated by the words and exploits of Irish patriots who had gone before him. He was particularly enthralled by Robert Emmet, whose short, failed rebellion against British rule in 1803 ended with his execution by hanging followed by beheading. Pearse owned a death mask of his hero and the block on which Emmet was said to have been beheaded—grim items for a school to display and stark reminders of the depth of Pearse’s commitment to the “die for Ireland” ideal.

Pearse went to the United States in the spring of 1914 to raise money for the school. For better or for worse, the US has long been a source of a radical Irish republicanism. Already drifting towards physical force nationalism, Pearse found compatible and even more radical supporters in New York. He came back to Ireland ready not only to support and participate in an insurrection, but to die in one. It is a chilling legacy for the school that so many St. Enda’s boys participated in the Easter Rising and numbered among the dead.

Pearse’s Cottage, Rosmuc, Co. Galway

Before this period of radicalization, Pearse bought a small cottage overlooking Loch Eiliarach in an isolated, Irish speaking part of County Galway. The cottage, Teach an Phiarsaigh, was his retreat for writing and thinking, and he often brought boys from St. Enda’s there for a Gaelic language immersion experience. Like many nationalists of his day, Pearse had found his way to revolutionary politics from cultural nationalism. His love of the Irish language led him to join the Gaelic League, and to write and teach in that language. The cottage at Rosmuc in its lovely setting in the woods above the lough commemorates the tranquil times of his life, when he was doing the work he loved in the language he helped revive.

After visiting the school Pearse founded and loved and the cottage at Rosmuc, I couldn’t help but regret the years of writing and teaching he foreswore when he and Willie set out to participate in the Easter Rising on Sunday, April 23, 1916.

The Stonebreakers’ Yard, Kilmainham Gaol

Pearse played a leading role in planning and carrying out the events of Easter week. He authored the proclamation that boldly declared Ireland to be a republic, and on Easter Monday, 1916, read it out loud in front of the General Post Office on Dublin’s main street, a focal point of the battle. The rebels were outnumbered and out-armed. By the end of the week, it was obvious that surrender was the only way to prevent massive civilian casualties and further destruction of the city. Following brief negotiations, Pearse surrendered on Saturday, April 29. The Easter Rising had lasted six days.

Under martial law, Pearse and hundreds more were rounded up and imprisoned; following rapidly convened and rigged court martials, ninety rebels were sentenced to death, though only sixteen executions were carried out. Fourteen of the “sixteen dead men” were executed at Kilmainham. The fifteenth, Thomas Kent, was executed in Cork. The sixteenth man in Yeats’s poem was Sir Roger Casement, executed in London in August of that year. On Wednesday May 3, four days after being arrested, Patrick Pearse was executed first, along with Thomas MacDonagh and Thomas Clarke, in the Stonebreakers’ Yard at Kilmainham Gaol.

Closed in the 1920s after a hundred and thirty years of housing political and other prisoners, Kilmainham has been restored and affords the best window into Irish history in all of Ireland. I never tire of viewing the independence struggle and the larger tapestry of history from this vantage point. Fourteen men were held here briefly before being executed, and there’s a sad story of each one’s last hours. The high stone walls and location of the Stonebreakers’ Yard made it impossible for anyone except the firing squad to see the executions. British army officials were concerned about turning the men they saw as traitors into martyrs. Today a simple black cross marks the spot in the yard where the men were shot, one by one, a piece of white cloth pinned over the heart. No place in Ireland, not even the mass grave for the fourteen at Arbour Hill Cemetery, sums up their legacy better.

At first the Rising was regarded as a spectacular failure, an episode of needless slaughter and destruction that strained the British army at a time of great peril—the middle of the Great War. Including solders and civilians on both sides, 466 died in the Easter Rising, while at the fronts in Europe and the Middle East, casualties were numbered in the tens of thousands daily. But the  summary executions in Ireland, technically part of the United Kingdom, contributed to a gradual but deeply significant shift in public opinion about the Rising and, more important, about the possibility of finally throwing off British rule. In 1921, following the War of Independence (also called the Anglo-Irish War), twenty-six of the thirty-two counties would achieve this goal, becoming the Irish Free State in that year and in 1949 the Republic of Ireland. Of course, it’s more complicated than that –it always is in Ireland—for a significant portion of the population believes that the goals of the Easter Rising will never be achieved until the six counties of Northern Ireland are reunited with the Republic, a turn of events that seems as impossible as the fall of the Berlin Wall seemed until November 1989.

summary executions in Ireland, technically part of the United Kingdom, contributed to a gradual but deeply significant shift in public opinion about the Rising and, more important, about the possibility of finally throwing off British rule. In 1921, following the War of Independence (also called the Anglo-Irish War), twenty-six of the thirty-two counties would achieve this goal, becoming the Irish Free State in that year and in 1949 the Republic of Ireland. Of course, it’s more complicated than that –it always is in Ireland—for a significant portion of the population believes that the goals of the Easter Rising will never be achieved until the six counties of Northern Ireland are reunited with the Republic, a turn of events that seems as impossible as the fall of the Berlin Wall seemed until November 1989.

William Butler Yeats captured the significance of these events in one of his most famous poems, “Easter, 1916,”: “All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.” Though the Rising was quashed, the transformation had begun. The sixteen executions were not the first deaths in the name of Irish independence, nor would they be the last. More than any of the rest, Pearse foresaw such an end as a necessary part of the drama to be played out and relished his own role in it. The deaths—the executions and the battle deaths—and the violence were terrible. Were they worth it in the end? Was the beauty of independence—long sought, hard won—fitting recompense for such sacrifice? Those questions continue to be debated here in Ireland and elsewhere.

Teacups said to have been used for the last time time by Patrick and Willie Pearse, just before they left St. Enda’s to join the Rising (Pearse Museum)

*The best biography of Patrick Pearse is the perfectly titled The Triumph of Failure by Ruth Dudley Edwards (1977, revised in 2006). Before this book was published, only hagiographic accounts of Pearse had been written. The guides at the Pearse Museum told me that this fair but unflinching look at Pearse’s life and times is their main reference.

Níl leagan Gaeilge ar fáil, an bhfuil?

Sadly I don’t speak Irish we; enough; I am still learning this difficult but beautiful language.

Dudley Edwards biography isn’t the best to be honest. It’s far from being the best actually.

True–since I wrote this essay, several other books have come out to tell Pearse’s story.