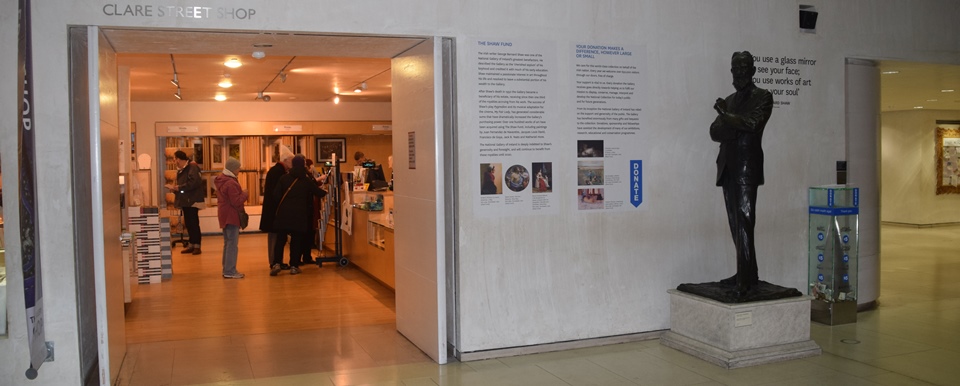

31 At the Museum

Posted by Christine on Jan 19, 2015 in Ireland | 2 comments

Rest on the Flight into Egypt with the Infant John the Baptist (1494) at the National Gallery of Ireland

I grew up in Evanston, Illinois, next door to Chicago, a city of world class museums. My parents, my aunt, and my elementary school would sometimes take me to visit the massive buildings on museum mile, but it wasn’t long before I was going regularly on my own, taking the “L,” walking along the lakefront and up one grand staircase or the other to wonder at the dinosaurs lurking in the lobby of the Field Museum, or to visit with American Gothic and A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte at the Art Institute, or to climb around on an actual German U-Boat at the Museum of Science and Industry.

Background information about all of these things and what they meant would come in time. What mattered then was being in the presence of greatness and stretching my mind, in all its youthful ignorance, to try to make sense of what I was seeing. Only years later did I realize that not everyone lived in a museum city or had access to such vast collections of the world’s natural history, art, and science.

Dublin is also a city of world-class museums, but Ireland’s national institutions have been struggling financially since the 2008 world crisis with no relief in sight. Every week the papers are full of the cutbacks and other indignities they’ve endured. When the head of the National Library of Ireland visited Emory University in Atlanta for a panel on Seamus Heaney in 2014, she told the audience that in spite of the exciting collection of Heaney materials donated by the poet shortly before his death, the NLI can barely afford to catalogue them, much less create an exhibit in the great poet’s honor. The National Museum of Ireland—including archeology and history at the Kildare Street location, natural history on Merrion Street Upper, decorative arts at Collins Barracks, and country life at Turlough in Co. Mayo—is considering reductions to hours, further cuts to staff, the closing of some sections or possibly the Mayo site, and the introduction of an admission fee. There’s been an outcry against charging admission, but that may be the only way to keep these important institutions running.

It’s ironic that at a time of remembering and celebrating momentous historical events in Ireland’s history—the so-called decade of centenaries that began in 2012 with the hundred year anniversary of the Irish Home Rule Crisis—the museums housing the relevant items and documents and where key exhibitions would logically take place are  facing drastic reductions to public access and even to the care and security of their collections.

facing drastic reductions to public access and even to the care and security of their collections.

Like many people, I found food for the imagination in the museums I could freely attend as a child, haunting their halls as I developed my own interests, ideas, and questions. Consider the example of George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), who grew up in Dublin, went on to write plays like Major Barbara, Man and Superman, Saint Joan, and everyone’s favorite Pygmalion. Among many other accolades, Shaw won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and an Oscar in 1938 for the screenplay of the film version of Pygmalion, the only person ever to earn both awards. Reflecting on his Dublin boyhood, Shaw credited the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI), Dublin’s main art museum, for “the only real education I ever got as a boy in Eire.”

The Shaws weren’t poor, but they lived beyond their modest means and had no money to spend on their son’s schooling, choosing instead to send him off to earn an income for the family. The young Shaw educated himself by going often to the great National Gallery on Merrion Square, taking advantage of the free admission to explore the history of ideas and their representation in the paintings and sculptures he found there. Among the works of the great masters and without a planned curriculum or anyone to guide him, Shaw let his imagination do the work. “You use a glass mirror to see your face” Shaw wrote later, “you use works of art to see your soul.”

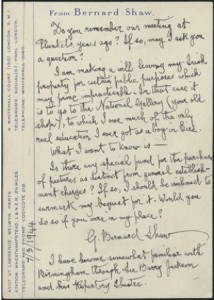

Shaw never forgot those days in the gallery, and when he had made some money from his plays and from the screenplay, he included the NGI in his will. During a “curator’s choice” event during Heritage Week last August, I saw the original postcard to the director of the National Gallery of Ireland by which Shaw first enquired about leaving money to the gallery. Shaw knew what was important: he wanted his money to go to the “purchase of pictures” and not “general establishment charges.”

Sharing royalties from all of Shaw’s plays with two other arts institutions (the National Gallery of Britain and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) turned out to be a huge boon for the Irish museum, especially when the musical version of My Fair Lady became an international hit on stage and screen. So far the gallery has been able to purchase over one hundred important works of art with the Shaw Fund, though because the copyright runs out in 2020 (seventy years after Shaw’s death), they, like the other Irish national museums, will also face a challenging financial future.

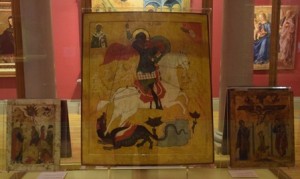

Miracle of Saint George and the Dragon at the National Gallery of Ireland, purchased by the Shaw Fund

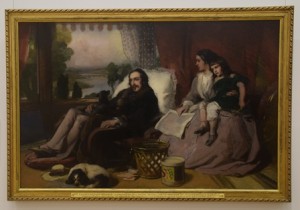

I love this story about the young GBS, bookish but not educated, working at a menial job to help support his family and feeding his hungry imagination in the gallery that was only about a mile from his house. Wandering through the NGI the other day, I noted some of the paintings that were in the museum when Shaw was living in Dublin. Did Francesco Granacci’s luminous Rest on the Flight into Egypt with the Infant John the Baptist (1494, above) stun him with its color and light, as it did me? Did Edward Henry Landseer’s Members of the Sheridan Family (1847) inspire the germ of an idea that later become a scene or a theme in one of Shaw’s plays? Scholars often study the books in a writer’s library, but they rarely get to ponder the paintings that shaped the author’s thinking.

The works of art the NGI has been able to purchase thanks to Shaw’s bequest show how powerful that influence can be. Jack Yeats’s famous Grief (1951, b elow), a devastating modernist commentary on personal and wartime mourning, hangs in the NGI thanks to the Shaw fund. With its dramatic action and fire-breathing monster, the fifteenth-century Miracle of Saint George and the Dragon (Novogorod School) grabs the attention of schoolchildren like the young Shaw as they walk into the gallery it dominates. Roderic O’Conor’s La Jeune Bretonne (1895) interprets the subject’s character in a work that poises on the edge between realism and abstraction. Shaw’s plays and other writings made a substantial contribution not only to literature, but also to the imaginations and future achievements of those who walk through the museum he endowed.

What great future scientists, doctors, painters, humanitarian leaders, or Nobel Prize-winning authors will be stymied in their intellectual and creative development because their families couldn’t afford the price of museum admission, or because their parents’ and grandparents’ generations have neglected the arts, forcing the great museums to close their doors?

(The photograph at the top of the page is the entrance to the National Gallery of Ireland with a statue of George Bernard Shaw next to his famous quotation about art.)

Beautiful examples of brilliance.I certainly hope that an art loving philanthropist steps up and provide financial assistance. I too grew up in a city rich in museums and was blessed as a child and young adult to experience the greatness that they offered.

Thanks Martha! We’ve got to keep museums free and exciting to inspire future Bernard Shaws and Martha Wallaces!