36 The Cabbage Gardens

Posted by Christine on Feb 23, 2015 in Ireland | 3 comments

Since researching the history of cabbage in Ireland for “33 Bacon and Cabbage,” I’ve been haunted by a place I visited for the story, a little grassy park near St. Patrick’s Cathedral here in Dublin known as The Cabbage Gardens or The  Cabbage Gardens Cemetery. It was on this site that starting in 1649, soldiers serving under Oliver Cromwell grew cabbages, or so the story goes. Eventually the land was used for an overflow cemetery for the nearby parish of St. Nicholas Without (meaning outside the city walls), a burial ground for French Huguenots who came to Dublin escaping persecution, and finally a city park.

Cabbage Gardens Cemetery. It was on this site that starting in 1649, soldiers serving under Oliver Cromwell grew cabbages, or so the story goes. Eventually the land was used for an overflow cemetery for the nearby parish of St. Nicholas Without (meaning outside the city walls), a burial ground for French Huguenots who came to Dublin escaping persecution, and finally a city park.

For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the layers of history—personal or public—that occupy the same space on earth. When I was very young I lived in a big old gray Victorian house in Evanston, IL, and even then I’d try to imagine the lives of past residents and where in the house or yard I might cross paths with their ways—not their ghosts, but their habits, their activities, their favorite spots. I used to search the bare boards of the large attic to see if they had left any messages for future generations to find. In the travel and creative writing I’ve done, this history of space has played a big part, perhaps to the point of obsession. I’m always trying to figure out where things were in the past, how that differs from or overlaps with the present, and what vestiges of the old ways and the old things we can still see. Part of the fun of studying writers or other historical figures is to haunt the houses they lived in, walk the streets they walked, gaze at the buildings or forests or mountains they knew. Even if the terrain and buildings have changed dramatically, you still learn a lot from inhabiting the spaces they inhabited. When I visited the farmhouse in County Down where Agnes Irvine Scott was raised, for example, I discovered she could see the Irish Sea from the field behind the house, a piece of information that had not previously come to light but that added to my understanding of her life in that place (see “15 The Mountains of Mourne”). Though I didn’t plan to do it, quite a few of my blog entries this year tell stories of me tracing the past in the present.

So after reading about the Cabbage Gardens, I had to see it, or what was left of it. On a bright but frigid Sunday afternoon, I made my way to St. Patrick’s with both an old and a new map in hand. I followed the street that runs along the cathedral to the south around past Marsh’s Library, St. Patrick’s Close, across Kevin Street and further south on the other side of the intersection where it becomes Cathedral Lane. Just a few hundred yards from Kevin Street, the park lies somewhat hidden amidst several banks of old and new brick apartment blocks, surrounded by a wall and overlooked by balconies with barbecues and laundry flapping in the wind. If you weren’t looking for it, you’d never know it was here. Even though there was nothing difficult or mysterious about finding this place, as the wall and gate and green sward of the park came into view I felt the thrill of successful sleuthing.

The online sources I’d read warned that the Cabbage Gardens was run down and neglected, but on that day at least, the park was well-kept and welcoming, a green oasis in the densely urban landscape. Roundish in shape, the park has a path around its edge, some nice trees and shrubs, and the grassy area in the center that the city bills as a “football pitch,” though it would have to be a fairly small-scale game with imaginary goal posts. But what makes this park unique is that along the east wall, hundreds of gravestones are stacked helter-skelter, some with readable inscriptions, others worn with time and weather. In the northeast corner there are more gravestones, a couple still in place, and a plaque commemorating the history of the Cabbage Gardens. Though most of the gravestones have been moved, according to the history of the place the dead still lie buried throughout the park with their resting places no longer marked and orderly. I presume there is no longer anyone left to care. From the grassy area, you can see the steeple of St. Patrick’s, at one time the center of life in this corner of Dublin and still an elegant neighbor.

The land here was on the fringe of medieval Dublin; even St. Patrick’s was outside the city walls, an important distinction at the time, making this area a community unto itself. By the mid-seventeenth century when Cromwell and his army arrived, the city was starting to spread in this direction. Cromwell’s invasion and conquest of Ireland on behalf of the English parliamentarian forces in the Eleven Years War began in 1649 and lasted about four years, though he stayed less than a year. His intention, which he achieved with a vengeance, was to reestablish control of Ireland, vanquish the Roman Catholic forces that had become powerful and were supporting the Royalists, his enemies, and secure more troops for his cause. Duped by rumors that the Irish had massacred English residents and driven by religious fanaticism, he waged a brutal war against both soldiers and Catholic civilians that some have likened to ethnic cleansing.

It’s hard not to agree. In justification of the siege of Drogheda where 3500 soldiers and mostly Catholic civilians were killed, Cromwell said,

This is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood….it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are satisfactory grounds to such actions, which otherwise work remorse and regret.

Cromwell believed Catholics were heretics. In addition to killing them whenever he could, he confiscated or destroyed their churches and possessions. He didn’t like the established church or the Presbyterians either. When his army occupied Dublin, to show his disapproval of the Church of England he used St. Patrick’s Cathedral as a stable for his horses. As you might guess, he is a hated figure in the Republic of Ireland, where recent scholarly attempts to soften his reputation have found little sympathy. And no wonder, for he probably did as much as anyone to deepen the divide between Catholics and protestants that has plagued Irish politics and society for centuries. In Northern Ireland he is recognized as a hero and defender of the faith by some on the extreme Loyalist side of the divide, as this mural from 2002 suggests, but in the Republic there are no statues or monuments celebrating Oliver Cromwell.

Cromwell believed Catholics were heretics. In addition to killing them whenever he could, he confiscated or destroyed their churches and possessions. He didn’t like the established church or the Presbyterians either. When his army occupied Dublin, to show his disapproval of the Church of England he used St. Patrick’s Cathedral as a stable for his horses. As you might guess, he is a hated figure in the Republic of Ireland, where recent scholarly attempts to soften his reputation have found little sympathy. And no wonder, for he probably did as much as anyone to deepen the divide between Catholics and protestants that has plagued Irish politics and society for centuries. In Northern Ireland he is recognized as a hero and defender of the faith by some on the extreme Loyalist side of the divide, as this mural from 2002 suggests, but in the Republic there are no statues or monuments celebrating Oliver Cromwell.

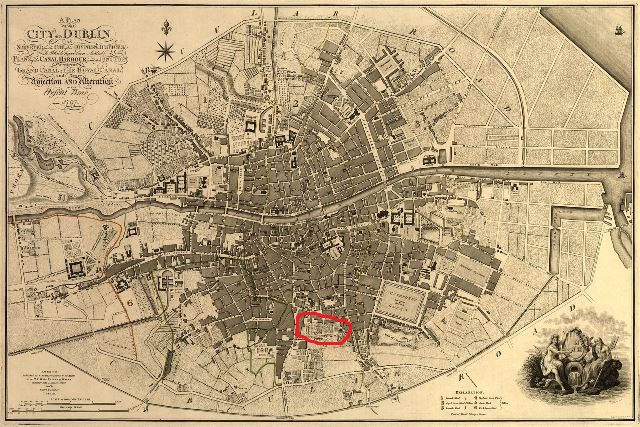

In 1649 Cromwell’s soldiers rented a plot of land south of St. Patrick’s and used it to plant cabbages, which were not grown in Ireland at the time. From this period onward, the Cabbage Gardens appears as an open space on maps of the city. In 1666 the nearby protestant parish of St. Nicholas’s ran out of burial grounds and bought the land to be used for a cemetery. Many famous local Dubliners were buried there, including John Huband, who was a director of the Grand Canal Company in 1791. In 1681 a small strip of the cemetery was granted to the Huguenots, French protestants fleeing persecution in their own country. The dean of St. Patrick’s had allowed them to use the Lady’s Chapel in the cathedral for their services. This gorgeous 1797 map of Dublin shows that even 150 years after the soldiers used it for their garden, the plot of land south of the cathedral—considerably bigger than it is now—was still called the Cabbage Gardens.

The name has stuck for over 350 years, though it’s almost that long since any cabbages were planted here. The cemetery was in use until 1858 but neglected after that, like so many of the protestant graveyards in the increasingly Catholic city. But the graves, marked or unmarked, kept the land from falling to the developers, something we can be grateful for today. In 1982 Dublin City Council designated the area a park.

I don’t think there are many apartment buildings in the city that overlook such a lovely green space. Even on the cold day I visited, dog walkers, children kicking a ball, and babies in strollers were enjoying the bright sun. I haven’t heard any tales of the garden-cemetery-park being haunted, but the kids playing there must have a lot of thoughts and perhaps some taunts to level at each other about the hundreds of gravestones shunted to the side, not to mention the hundreds of bodies beneath their feet.

All the layers of history are still visible in the Cabbage Gardens—all but one. I really think the city ought to plant an ornamental strip of cabbages somewhere in the park to honor its humble origins and its enduring name.

i loved this post! Yes, I see clearly that this is a story of you and your passion for place and meaning, and I so enjoy sharing your adventures through your blog. I’ve always despised Cromwell and his despicable crusade in Ireland, but I feel the pull of history to know the space he occupied while there. My next trip to Dublin (with hope that there will be one) will include a visit to the Cabbage Gardens, not so much to seek out the spirit of Cromwell’s soldiers or those that lie underneath the ground, but to remember your visit and the love of Irish history that took you there!

Thank you Susan! I look forward to hearing tales of your second trip to Ireland. Maybe we can meet up somewhere!

This line of yours seems to capture much of what I have been reading: “the thrill of successful sleuthing.” Still enjoying every post. -Kathi