37 Cows in the Library

Posted by Christine on Mar 2, 2015 in Ireland | 3 comments

Those are Yeatsian cows in the picture above. They graze on the plain “Under Ben Bulben,” the same plain where St. Columba fought “the Battle of the Book,” on the other side of the stone wall from Drumcliff Churchyard, where the poet William Butler Yeats is buried (see “33 Under Ben Bulben”). On a brilliant sunny day last August, I found them there unwittingly adding to the peacefulness of the scene. When cows are not grazing, they do something else that’s important to their health and digestion: they chew their cud; they ruminate.

From Merriam Webster online…

Ruminate

transitive verb

1: to go over in the mind repeatedly and often casually or slowly

2: to chew repeatedly for an extended periodintransitive verb

1: to chew again what has been chewed slightly and swallowed: chew the cud2: to engage in contemplation

The other day at a lecture on Yeats and the National Library of Ireland, I heard a fascinating story about him, one he recounts in the 1933 preface to Letters to the New Island, a collection of essays on literary and cultural themes first published in 1933. The “New Island” is, of course, Ireland in the post-independence, post-partition, post-trauma era. Yeats remembers sitting in the reading room of the National Library—the same one on Kildare Street where I go to do research and to read—in the 1890s when he was twenty-six or -seven, day-dreaming over a book, when “some old man, a stranger to me” said to him, probably in a stern and peeved tone, “’I have watched you for the past half hour and you have neither made a note nor read a word.’” As Yeats explains, the old man “had mistaken…me for some ne’er-do-weel student.”

Though the young and ostensibly idle Yeats was not yet the Nobel Prize winning poet of world renown, he was already writing, publishing, and editing poetry. Poems such as “The Lake Isle of Inisfree,” “The Stolen Child,” and “Down By The Salley Gardens” and many others had come out in magazines and in books by this time. At the moment when the old man called him out, he was working on editing a volume of William Blake’s poetry for publication. Whatever Yeats’s distraction from a more visibly “appropriate” library task, there are critics and biographers even now who would love to know the substance and range of his thoughts as he sat there in the gloriously elegant reading room—a room that with its round walls, oak furniture, shelves full of books, and mind-freeing robin’s egg blue dome seems to have been made for day-dreaming. What poem or play or essay was churning around in his mind at that moment? Was he working out some of the “rose” poems as he sat there hunched over a book in the reading room? Was he pondering the plot outline for the play Cathleen Ni Houlihan, the play he later feared had sent young men out to die for Ireland? As he sat there gazing into space, he could have been searching for the words for one of his many love poems to Maude Gonne. Or was he simply day dreaming, letting his mind wander until it found a place to rest?

The Reading Room of the NLI with a glimpse of the dome (photography was not allowed inside–further protection for day dreamers?)

The librarian who recounted this anecdote noted that we can never know the quality of others’ idle musings in the library (or elsewhere) and should respect those moments—make room for them and protect them if we can, as librarians around the world try to do. A librarian would never have admonished Yeats for being lost in thought in the library as the curmudgeonly man did—that’s what a library is for! Her words were a wonderful endorsement of libraries and the free thought that can and should take place in them surrounded by, inspired by, but also transcending the books, periodicals, and other resources that these institutions preserve and cherish. Her words are also important words for writers to take seriously.

Giving yourself time to let the mind wander, play, or deepen its focus can be a very hard thing to do. It looks so much like you’re doing nothing! And when a deadline looms, time spent not actually writing or at least editing becomes even harder to justify. And yet, very often the big important leaps in thinking—the insights or phrases or twists and turns that will make a real difference to the piece—only come when you’ve turned away from the web of words and let your guard down.

Allowing myself to have time to ruminate, time to think away from the writing and not necessarily focused on the writing, is the hardest of all steps in the process for me, the one I feel guiltiest about. If I’m not chained to the computer, if I didn’t make my word count, if I’m not actually writing, am I really working? Yet looking back on a finished piece, something I’m proud of or that speaks to others in some part the way I hoped it would, I can see that it’s the moments of rumination that gave the work its added depth or edge, that took me to another level in my understanding of what I was doing and in my ability to do it.

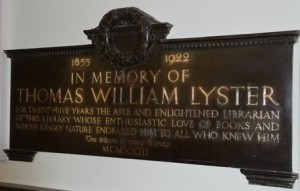

Yeats valued his time spent in the library and the librarians who helped him find the materials he needed and protected his right to occupy one of those comfortable oak chairs under the blue dome working on a poem or an editing job—or lost in thought. He often wrote about how important the library was to him. The head librarian during most of Yeats’s adult years was Thomas William Lyster  (1855–1922, at the NLI 1895-1920), whom many patrons praised for his solicitousness of their reading needs. He appears in James Joyce’s Ulysses and in the writing of surgeon and poet Oliver St. John Gogarty. Lyster welcomed all to use the library, and even defended the right of students from a nearby university to congregate on the steps when others railed against the practice, saying “they must be allowed to sit there, because this is their building.”* Yeats wrote a memorial praising Lyster’s encouragement of readers and copy for the plaque commemorating the beloved librarian that still hangs outside the reading room.

(1855–1922, at the NLI 1895-1920), whom many patrons praised for his solicitousness of their reading needs. He appears in James Joyce’s Ulysses and in the writing of surgeon and poet Oliver St. John Gogarty. Lyster welcomed all to use the library, and even defended the right of students from a nearby university to congregate on the steps when others railed against the practice, saying “they must be allowed to sit there, because this is their building.”* Yeats wrote a memorial praising Lyster’s encouragement of readers and copy for the plaque commemorating the beloved librarian that still hangs outside the reading room.

Every time I make my way to the reading room in the National Library, I think about the great poet day dreaming at one of the tables and the modern librarian’s defense of his and others’ right to do so–a reminder to grant myself that same freedom as often as possible. All of us–readers, writers, and thinkers–should permit ourselves moments of rumination wherever and whenever we may need them to solve an ongoing problem, come up with better words or means, seek a direction that is entirely new, or find from our temporary escape to dreamland renewed energy to carry on.

*The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats Vol X: Later Articles and Reviews, Richard J. Finneran and George Mills Harper, eds. Simon and Schuster, 2000, p. 209.

I love how Irish tour guides and proprietors (even taxi drivers) add so much to the experience by sharing wee stories and anecdotes. You, in turn, do the same thing in each blog. BTW, my rumination place is the shower, and the pounding hot water, I suppose, is the librarian protecting me from interruption. Thanks for speaking to the writers.

Love this post! Having ruminated in the main branch of the New York Public Library this fall, I endorse your recommendation wholeheartedly. Naturally, this also prompts me to wonder whether a cultural disposition to or tolerance of ruminating explains the extraordinary number, per capita, of notable Irish writers and other artists. A NYT article from 2010 connects ruminating to an evolutionary theory of depression that casts it as a net benefit to the individual. The article says in part: “Why is mental illness [i.e., supposedly made worse by pointless ruminating] so closely associated with creativity? Andreasen argues that depression is intertwined with a ‘cognitive style’ that makes people more likely to produce successful works of art. In the creative process, Andreasen says, ‘one of the most important qualities is persistence.’ Based on the Iowa sample, Andreasen found that ‘successful writers are like prizefighters who keep on getting hit but won’t go down. They’ll stick with it until it’s right.’ While Andreasen acknowledges the burden of mental illness … she argues that many forms of creativity benefit from the relentless focus it makes possible. ‘Unfortunately, this type of thinking is often inseparable from the suffering,’ she says.”

Thanks for commenting, Jim! It means a lot to me that you are reading my blog.