40 Bursting Fetters, Striking Off Chains

Posted by Christine on Mar 23, 2015 in Ireland | 1 comment

Though I didn’t realize it until later, earlier this year I stood on the spot where two of the world’s greatest human rights leaders, Daniel O’Connell and Frederick Douglass—one an Irishman at the end of his career, the other an American at the beginning of his—met and conversed for the first and only time on September 29, 1845.

In an earlier post, “38 Waiting in Line To Be Legal,” I wrote about the day Ron and I spent at the Irish Immigration and Naturalization Service (IINS) office on Burgh Quay in Dublin trying to straighten out our visa situation. Located in a choice spot overlooking the river and only a block from O’Connell Bridge where the statue of Daniel O’Connell, known as “The Great Liberator,” presides, the ugly modern building with its subdivided structure and cheap materials was clearly built for bureaucratic purposes. I didn’t think much about the building at the time, but I did notice that the adjacent structures, clearly Georgian in style, were much nicer.

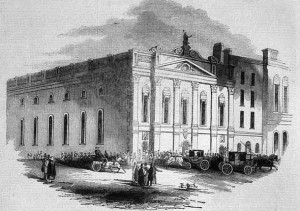

Then a few weeks ago I made a discovery after reading Tom Chaffin’s book about Frederick Douglass’s 1845 trip to Ireland, Giant’s Causeway: Frederick Douglass’s Irish Odyssey and the Making of an American Visionary and digging around in some online archives. It turns out that the IINS building, the very same building where visitors and immigrants come to seek legal status in Ireland, stands on the site of “Conciliation Hall,” erected in 1837 by an organization dedicated to repealing the Acts of Union. The Acts of Union, passed by the British parliament in 1800 and put into effect on January 1, 1801 in retaliation for the 1798 Rebellion, closed the Dublin based Irish parliament and placed control of Ireland’s affairs with Westminster, far removed from the country’s problems and needs and further disenfranchising the country’s largely Catholic population. O’Connell was the leader of the repeal movement in 1845 and was speaking in Conciliation Hall on September 29 when Douglass–a former American slave and author of an account of his life under slavery (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass An American Slave. Written by Himself) who had arrived in Dublin a few weeks earlier–walked in.

I had known about their famous meeting for a long time–Willie Tolliver and I always discuss and commemorate it with the Agnes Scott students we bring to Ireland–but until recently I had not known Dublin well enough to grasp the details of where it actually occurred. Compare the two images below: an old drawing of Conciliation Hall and a photo I took a few weeks ago of the IINS building located at the same corner of Burgh Quay. While the modern building replaced Conciliation Hall, the two buildings next door are the same in both pictures: the narrow building to the right and the wider building with two rows of large windows further to the right, both modified over the years but still standing. Following its role in the repeal movement, the Conciliation Hall building was used to house first a concert hall, then the Tivoli Theatre–its large assembly room with room for a thousand would have been perfect for such venues–and later a newspaper office. Sadly, the magnificent structure was torn down some time in the mid twentieth century. Conciliation Hall and today’s IINS building, though differing in size and shape, occupy the same corner and river frontage and share an overlapping mission to address basic human rights for visitors to and citizens of this country, though it must be said, the IINS could learn a lot from O’Connell and his broadly inclusive philosophy of human rights.

Though my stay in the IINS building last December was long and tedious, I now consider it an honor to have trespassed on the very space O’Connell and Douglass inhabited 170 years ago. In our preparatory course and on the student trip, Willie and I have always commemorated this event at O’Connell’s former home in Merrion Square, an elegant Georgian building today owned by the University of Notre Dame and used for its study abroad program. While we will still pay homage to the Great Liberator on this spot, we’ll have to add the site of Conciliation Hall to our Dublin sightseeing and read aloud from the eloquent letters Douglass wrote about his tour of Ireland as we stand on Burgh Quay.

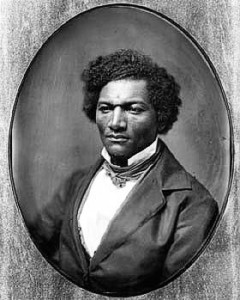

With their common interests in human rights and the abolition of slavery, Daniel O’Connell and Frederick Douglass were destined to meet, and friends negotiated their introduction on that September day. Douglass was determined to come to Ireland and Britain for reasons he outlined in the preface to the second Dublin edition of his narrative. He wanted to “be out of the way during the excitement consequent on the publication of my book” lest his former “owner” take legal action against him. He also sought to “increase my stock of information, and my opportunities of self-improvement, by a visit to the land of my paternal ancestors.” And he wanted to gain further support for the abolition movement in the United States, in order to achieve

the overthrow of the meanest, hugest, and most dastardly system of iniquity that ever disgraced any country laying claim to the benefits of religion and civilization.

When Douglass arrived in the vast hall, O’Connell was speaking, and according to Douglass, the Irishman’s oratorical gifts had not been exaggerated. On this occasion, Douglass himself took to the podium and said a few words. An account in the Freeman’s Journal the next day paraphrased Douglass’s remarks, including his praise of O’Connell’s denouncing of slavery and its resonance in the United States:

For while with one arm the Liberator was bursting the fetters of Irishmen, with the other he was striking off the literal chains from the limbs of the negro (cheers).

O’Connell and Douglass were deeply impressed with each other, but as far as we know, this meeting in Conciliation Hall was their only encounter. Douglass went on to give more speeches in Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Limerick, and Belfast and sold 2000 copies of his book during his successful tour of Britain and Ireland. In later years he looked back upon the trip with gratitude and a sense of its importance to his career.

Throughout the course that prepares students for the three week study trip, Willie and I draw many parallels between the American experience and the Irish experience, particularly emphasizing the struggle for independence from Britain that both countries endured and the very similar civil rights movements, one on behalf of African Americans in the US and the other on behalf of Catholics in Northern Ireland. In both countries civil rights has a long history, and the exchange of ideas, strategies, rhetoric, and heroes goes back even further than the two great liberators There are many parallels and intersections to examine. In modern times, the twentieth-century Irish civil rights movement was purposefully modelled on the American one that had gotten under way just a bit earlier, as Willie shows with photographs, film clips, and examples of the language of the movement from both countries.

O’Connell, a Catholic from the remote southwest of Ireland who was both a great intellect and a gifted orator, was to nineteenth-century Irish Catholics what Martin Luther King Jr. was to modern African Americans: using nonviolent means, he fought for Catholic rights at a time when they were barred from holding office, owning property or businesses, voting, practicing their religion, and much more. When these “penal laws” were finally revoked by Parliament in 1829, largely thanks to O’Connell’s efforts, the great orator turned his attention to repealing the Acts of Union. O’Connell masterfully organized the Irish people to work together towards both of these ends, and as a man opposed to violent rebellion, was one of the first world leaders to employ civil disobedience as a political tactic. Henry David Thoreau, Ghandi, and King all knew and admired his work, as did many nineteenth-century Americans pursuing the cause of human rights. O’Connell was also an outspoken opponent of slavery and was associated with the abolitionist cause in Europe and in North America. In early nineteenth-century America, there was even talk of the need for a “Black O’Connell” to emerge as a leader of abolition movement in the place where slavery was most firmly institutionalized.

Frederick Douglass, also known for his oratory and his intellect, was twenty-seven when he came to Ireland in 1845. In our course, Willie gives a lecture on Douglass’s life and Irish sojourn, telling the students how he came here on the recommendation of many friends to flee persecution in the US after publishing his account of his life as a slave earlier that year, as he was a wanted man in some parts of the US. Ireland was the first stop on a two year tour that also included Britain, during which he oversaw the publication of his book in Dublin and gave lectures about his experiences and about slavery in general. Though he arrived in Ireland on the eve of the famine in 1845 and found lamentable poverty everywhere he went, Douglass was deeply impressed with how he, a person of color and a former slave, was treated in Ireland. At the end of his trip, he wrote the following passage at his hotel in Belfast.

Excerpt from Frederick Douglass Letter to William Lloyd Garrison, January 1, 1846

Printed in The Liberator, March 1846I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life. The warm and generous co-operation extended to me by the friends of my despised race—the prompt and liberal manner with which the press has rendered me its aid—the glorious enthusiasm with which thousands have flocked to hear the cruel wrongs of my down-trodden and longenslaved fellow-countrymen portrayed—the deep sympathy for the slave, and the strong abhorrence of the slaveholder, everywhere evinced—the cordiality with which members and ministers of various religious bodies, and of various shades of religious opinion, have embraced me, and lent me their aid—the kind hospitality constantly proffered to me by persons of the highest rank in society—the spirit of freedom that seems to animate all with whom I come in contact—and the entire absence of every thing that looked like prejudice against me, on account of the color of my skin—contrasted so strongly with my long and bitter experience in the United States, that I look with wonder and amazement on the transition.

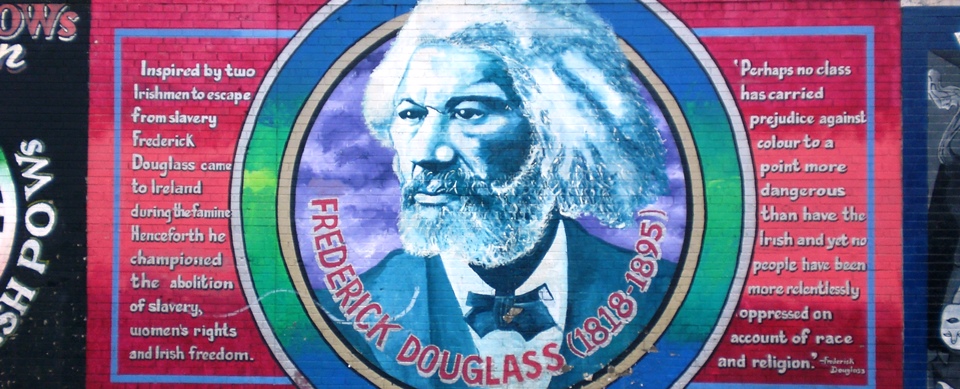

The O’Connell-Douglass meeting and the lives and works of both figures are central to the history of human rights in their own countries and around the world. While O’Connell would die only two years later—and seventy-five years before Ireland would achieve self-government—Douglass lived for half a century more, witnessing a terrible Civil War and the constitutional end of slavery in the United States, if not the vanquishing of its trauma, and playing an important role in the unfolding drama of civil rights. In the twentieth century, Douglass was invoked again and again in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and his image and words have appeared on several of the political murals commemorating the civil rights movement there (see photos at top and below).

The dreams the two men articulated and fought for have made progress but are still unfulfilled. Their legacies continue to inspire human rights activists. The name of their meeting place in Dublin, Conciliation Hall, is unusual in its truncation—in modern English we tend to think of the re-conciliation of opposing views—and humbling in its simple recommendation of a peaceful and loving effort to end strife and achieve human dignity.

It’s a shame that Conciliation Hall is no longer standing—it could have served as a fitting memorial to the forces for human liberty that came together on September 29, 1845.

Mural depicting Douglass and other human rights leaders including Daniel O’Connell (top center, immediately to the right of Douglass) Belfast, Northern Ireland

Sources

Chaffin, Tom. Giant’s Causeway: Frederick Douglass’s Irish Odyssey and the Making of an American Visionary. University of Virginia Press, 2014.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass An American Slave. Written by Himself. Second Dublin Edition. Dublin: Webb and Chapman, 1847 (copy in the National Library of Ireland).

The Frederick Douglass / Daniel O’Connell Project

Methodically working backwards in time through your fascinating and entertaining posts, and am more or less repeating a comment that I made on a more recent one. To wit, I needed your blog before reading novels such as Colum McCann’s *Transatlantic*, in one section of which he writes about Douglass’s 1945 tour. Fascinating to learn that O’Connell was a very early advocate of nonviolent means to effect change (how did I not know this already?). On that topic, I wish you had been able to be in two places at once, so that you could have heard John Lewis’s talk at the Paideia School last month.