41 Not Just a Postbox

Posted by Christine on Mar 30, 2015 in Ireland | 4 comments

When Ron and I were in Cork a few weeks ago, we stopped on one of the city’s main streets to take a photograph of a postbox—what we call a mailbox in the US—when a couple about our age, laden with shopping bags and obviously walking home with their groceries, stopped to talk to us. As I moved around to get just the right angle on the postbox, their bemused expressions pretty much told me what they were thinking.

“Excuse me,” said the man kindly, as one might talk to an old lady doing something embarrassing in public, “but it’s just a postbox.”

We laughed. We’re used to people staring at us incredulously when we take pictures of postboxes in Ireland; I have a folder full of such photos on my computer.

“Actually,” I said politely, pointing to the V R below the mail slot, “it’s not just a postbox; it’s a postbox that was put here during Queen Victoria’s reign and painted green in 1922.”

“So it is!” they exclaimed, suddenly interested. “We never noticed that before,” said the woman, wanting to make up for her husband calling us out.

I explained that my husband collects stamps, and so we are interested in postal history. “Thanks for showing us something about our city!” were their parting words.

No matter who you are or where you live, you can always learn something about your home from outsiders who see it with different eyes. But the story of Irish postboxes is a particularly interesting one, fraught with political meaning, as so much on this island tends to be.

In January of 1922, after a two year War of Independence with Britain and a six month truce during which treaty negotiations had taken place, the twenty-six counties that today make up the Republic of Ireland abruptly found themselves to be an independent entity that would be called the “Irish Free State.” The British army and government officers immediately started the process of pulling out, leaving the new provisional government to manage the transition. The Irish were eager to prove their ability to run a state and made a number of adaptive moves while more long term plans, including a new constitution, were in the works. But while other governmental activities could be hammered out over the coming few months, the mail had to be delivered day in and day out without interruption. How was that very important task to be accomplished?

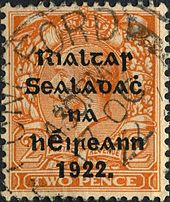

Temporary measures went into effect almost immediately. Within a few weeks following the handover of power, British postal stamps with King George IV’s image on them were overprinted with  “Rialtas Sealadaċ na hÉireann 1922” meaning “Provisional Government of Ireland 1922.” Overprints like these–and later ones that said ” Saorstát Éireann 1922″ or “Irish Free State 1922”–were the only stamps available until December of that year, when the first set of Irish Free State definitives was released. On these beautiful stamps the use of symbols such as the harp, the shamrock, the Celtic cross, Celtic designs from the Book of Kells, and the red hand of Ulster in the coat of arms, along with the Gaelic language and the map of Ireland with no border dividing north and south forcefully proclaimed the political outlook of the new state.

“Rialtas Sealadaċ na hÉireann 1922” meaning “Provisional Government of Ireland 1922.” Overprints like these–and later ones that said ” Saorstát Éireann 1922″ or “Irish Free State 1922”–were the only stamps available until December of that year, when the first set of Irish Free State definitives was released. On these beautiful stamps the use of symbols such as the harp, the shamrock, the Celtic cross, Celtic designs from the Book of Kells, and the red hand of Ulster in the coat of arms, along with the Gaelic language and the map of Ireland with no border dividing north and south forcefully proclaimed the political outlook of the new state.

The entire identity and presence of the Royal Mail had to be revamped in the new state, and that included thousands of bright red postboxes. The postbox had been introduced to Britain in 1855 by none other than Anthony Trollope the novelist, whose work in the postal service had taken him to the Channel Islands where they were already in use, having been brought over from France. Soon bright red postboxes with V R for Victoria Regina on them were set up all over the UK. Between 1855 and 1922, two more monarchs sat on the British throne ruling the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland”: King Edward VII from 1901 to 1910 and King George IV, who was king in 1922 when the Irish Free State came into being. Under each king, more postboxes with the royal mark were manufactured and distributed.

As soon as the Irish Free State was established, all around the twenty-six counties the red pillar-boxes and wall-boxes for posting letters were painted bright Irish green, the color chosen to signal the new postal service and the new state. Eventually, brand new green postboxes with no royal monogram would be manufactured and set up at postoffices and on the streets. But the pre-1922 postboxes were solidly made, and it must have seemed easier in some cases to leave the old ones in place, particularly when they were built into stone walls.

So today, even though the days of British rule and the Royal Mail are long gone, here and there in towns and villages all over this country you can find three kinds of overpainted postboxes in addition to the post-1922 variety. When we’re visiting a new place, we have a lot of fun hunting down a “Victoria,” an “Edward,” or a “George.” It is said that if you scratch the surface of one of these, the old red paint can still be seen.

In the US we don’t necessarily think of postboxes as political statements, but wherever sovereignty is disputed, they certainly are. During the Troubles in Northern Ireland (1969-1998), there were several incidents of IRA vandals painting green the red Royal Mail postboxes marked with with E II R (Elizabeth II Regina).

Today, many of the modern postboxes in the Republic of Ireland are also out of date. In 1924 the department of “Puist agus Telegrafa”(Post and Telegraph) was set up as the official mail service of the Irish Free State and, starting in 1948, the Republic of Ireland. Postboxes manufactured between then and 1984 bore the logo P&T or P+T. After 1984, the two branches of the service became separate, An Post and Telecom Éireann. Today’s postboxes are green and box-like with no monogram.

In the US, it’s rare to see a mailbox on the street these days. In most places you have to go to the post office to mail a letter, or you can give it to your mail carrier. That is also starting to happen in Ireland. As we move towards more and more electronic means of communication, these sturdy and sometimes beautiful artifacts are disappearing, and along with them, the histories to which they bear witness.

Enjoyed the piece Christine

Fascinating, Christine!

I thought myself to be a keen observer – but that is truly interesting. It goes (for me) hand in hand with the manhole covers…

I was reading the Book Banal Nationalism and the idea that every time we spend money, see a flag or everyday activities like posting a letter we are subconsciously reinforcing our national identity. Then as a duel Irish-British national, former postal worker and postgrad history student I thought f@&k me they painted the boxes green! Which happily brought me to this blog. As Hobsbawm stated nation-states invent traditions with supposed mythical ancestry and as Anderson said they are just Imagined communities. Perhaps this imagined tradition is painting post boxes with red or green paint. But nations and nationality fill humans with emotions e.g just look at the crying the players do at an international rugby or soccer match during the national anthems. Hopefully the idea of the nation state, a product of modernity that people are enthusiastically willing to kill or to die for will one day come to an end. Peace and love.