42 Alice M. Cashel–A Fenian at Heart

Posted by Christine on Apr 6, 2015 in Ireland | 25 comments

To the Fans and Relatives of Alice Cashel,

Thank you for your interest in Alice Cashel’s story. I am giving a talk on her during RTE’s “Reflecting the Rising” event on Easter Monday, 28 March 2016. Following that. I will post a revised version here with new information and resources. Please get in touch with me if you have memories or information about her you would like to share.

Thank you!

Christine Cozzens

Ireland is in the midst of a “decade of centenaries” commemorating an array of historical events that left a mark on the country from the Home Rule crisis of 1912, to the Dublin Lockout of 1913, the Great War from 1914 to 1918, the Easter Rising in 1916, and the struggle for independence that culminated in 1922. Almost every week there’s another anniversary, another shadowy corner of history opened to the light of modern scholarship and debate.

I’ve encountered these commemorations everywhere this year as lectures, exhibitions, renovations, conferences, ceremonies, new books and films, and more. It’s exciting to be here at this time as the Irish confront the past and try to understand not only what actually happened, but also why it’s important to today.

One strand of this era of commemorating and revisiting the past is bringing to light some of the lesser known participants in the independence movement, the women, whose stories are only now getting the attention they deserve.

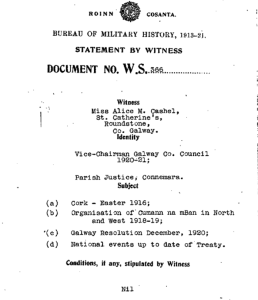

Alice M. Cashel (1878-1958) was one of these revolutionary women. A committed and energetic supporter of rebellion in Ireland from the moment she joined the Sinn Féin party in 1907, she gave her whole life to the cause of Irish independence. To name just a few of her roles, she served as a political organizer, a spy, an educator, a Sinn Féin judge, a finance specialist, vice-chairwoman of the Galway County Council, and author of a pro-rebellion young people’s novel The Lights of Leaca Bán that was taught in schools in the early years of the fledgling Irish Free State.

In the course of supporting an independent Ireland, Alice worked beside many of the leaders and notables of the Easter Rising and the War of Independence including Eamon De Valera, Constance Markievicz, Terrence MacSwiney, Arthur Griffith, Erskine Childers, Bulmer Hobson, George Nobel Plunkett, Sean Heggarty, Alice Stopford Green, Ada English, Kevin O’Higgins, Seán MacEntee, and W. T. Cosgrave. Given the times, she was remarkably mobile. Her activities took her all around both southern and northern Ireland, often on a bicycle and very often on the run from the police or the infamous Black and Tans, auxiliary soldiers the British employed to quash revolutionary activity in Ireland. From reading her own account of what she did during this period, I was intrigued by Alice’s sense of humor, her initiative and toughness, and her indomitable spirit.

I met this remarkable woman through a project I did for an adult education course on the Irish War of Independence 1919-1921 I’ve been taking this spring, a follow-up to a course on the Easter Rising of 1916 I took from the same instructor, Dr. Richard McElligott, in the fall. I’ve loved these courses, not only for the wealth of information Richard offers us, including visits to the archives at the National library of Ireland where the course meets each week, but also for the opportunity to meet and talk with the other students, Irish men and women who love history and want to keep abreast of modern scholarship. Their questions, stories, and insights have taught me a lot about how the past has played out in the present and about the diverse range of reactions to the events we have studied together.

To inspire class members to do research of their own on the individual stories of the revolutionary period, Richard told us about two incredibly rich online sources: the Bureau of Military history’s witness statements, collected in the early 1950s from surviving participants in the independence movement but only made available in 2003; and the Military Archives Pensions Collection, records from those who served in the wars and applied for pensions, made available in 2014. He asked us to dive into the collections, see what we could find, and report to the class.

Many people in the class had parents, grandparents, or other relatives or neighbors who participated in the independence struggle, an obvious place to start their research. I didn’t have that angle, so I started with reading accounts written by some of the famous people who intrigued me, then moved on to searching for women’s names in the alphabetical index to the witness statements. Scrolling through, I soon came upon Alice M. Cashel in the C’s, and once I started her story, I couldn’t stop reading. Fortunately for me, one of her descendants has put together a fascinating genealogy site that includes pictures of Alice and her family. I had a lot of material to work with in investigating her story.

Alice grew up in Limerick and Cork; it was in Cork where her friendship with the politically well-connected MacSwiney and MacCurtain families and her ability to speak the Gaelic language brought her into contact with the growing cultural nationalism movement and organizations like the Gaelic League that would prove to be incubators for rebels. She joined the new political party Sinn Féin the year it began. She heard about plans for a “rising” shortly before Easter in 1916 and was eager to participate. As a member of Cumann na mBan, the women’s organization allied with the all male Irish Volunteers that served as the rebel “army” of the rising, she was given a job to carry out.

On Good Friday, Alice received orders to “assume a good Protestant name” and go to a local garage to order several cars. Of course, the garage was closed in observance of the holy day, a mistake that typified the poor planning characteristic of the ill-fated rebellion. She later found out that the cars were supposed to transport arms to support the Rising that were going to be landed in County Kerry from a German submarine. The operation failed and resulted in the execution of its mastermind, the famous diplomat and humanitarian Sir Roger Casement.

Alice talked about the sense of frustration that prevailed in Cork as the Easter Rising unfolded in Dublin. As the Cork rebels waited, no orders came for the Volunteers and their supporters, who were ready and eager to act. She was clearly a woman of action, ready to do her part whatever it might be and wherever it might take her.

Following the Rising and the summary executions of sixteen of its leaders, Casement among them, that turned public opinion in favor of “physical force nationalism,” Alice was given another important job. In August 1916 she was asked to carry a written account of the Rising to the powerful John Devoy, a leader of Clan na Gael in the Unites States. Throughout the independence struggle, support and funds from America were crucial to the success of efforts in Ireland. Though she was questioned by the authorities upon arrival in the US because she was carrying documents in the Gaelic language, Alice was able to accomplish this task. In her statement she reports Devoy’s frustration with the turn of events in Ireland:

“I remember Devoy talking very bitterly of Casement and the organisation at home, saying that they seemd [sic] to think that they in America could do nothing.”

For the next several years, the forces of rebellion turned to political action, and Alice traveled all over Ireland campaigning for Sinn Féin candidates in the elections of 1918 and setting up branches of Cumann na mBan. In Clifden, Co. Galway, Alice got a chance to show her mettle. Here is the story in her own words:

“In August 1919 I was ordered to go to Clifden to organise Cumann na mBan. Orders had been sent from Sinn Fein H.Q. that on the 15th August a manifesto should be read in public by every Sinn Fein club in the country. On the morning of the meeting I was informed by one of the local R.I.C. [Royal Irish Constabulary] that if I held the meeting I should be arrested. We held the meeting near the square, it was broken up by the police the platform planks on barrels being pulled from under our feet. We stayed on until the last plank was taken. Then I reorganised the women in the street and marched them out of the town and held my meeting on the monument base which stands on a hill outside Clifden. While the police followed me the Secretary of the Sinn Fein club finished the reading of the Manifesto. I then had to ‘go on the run.’”

Darting around the countryside on her bicycle, Alice tried to avoid contact with the police as she was now on their “wanted” list. As the War of Independence got under way, and rebel attacks on the police and army as representatives of  British rule increased, Alice did what she could to help the cause, including serving as a Sinn Féin judge in the alternative courts that were set up all over the country to undermine the British justice system. These courts often had to meet at night and in secret places to avoid arrest.

British rule increased, Alice did what she could to help the cause, including serving as a Sinn Féin judge in the alternative courts that were set up all over the country to undermine the British justice system. These courts often had to meet at night and in secret places to avoid arrest.

“I got a message to meet certain volunteers at Toombeola, about three miles distant, at midnight and that they would bring me to Roundstone where a court was to be held. I cyc1ed to Toombeola and was met by volunteers as arranged, and we went on to about a mile or go outside the village where we left our bicyles [sic] by the roadside. We climbed over walls into the fields and so bye-passed the village where the police still lived (incidentally in the house which I now peacefully occupy). At length we arrived at a small stone building apparently standing alone in a field, but actually in a graveyard as I learnt later. The other justice, John Cloherty, had already arrived. Then the prisoners were brought in, blindfolded. They had been held on charges of larceny. We adjudicated on the cases and I remember convicted in one instance but found the other case not proved. We prisoners were led away and set out for home. We came back by a different way and to my surprise I discovered that we were in the grounds of the Fransciscan Monastery. The court had been held in the mortuary chapel (now demolished) in their graveyard.”

Alice recounts many adventures like this one in which she took risks to serve the cause. At this time she was living in her brother-in-law’s house, Cashel House (see photo at top), near the Twelve Bens in Connemara. On one occasion, the house was raided, and Alice and a companion escaped out the back window and into the woods where they spent most of the night in hiding. She was jailed and released several times. Always willing to be of service to the rebels, she talks about bringing orders from the Sinn Féin Council to the Galway membership, hiding the papers in her hair to avoid detection. She also lodged local rates or tax monies in her own account so that the funds could be kept from the British government and accessed by Sinn Féin.

Alice’s luck ran out when she took a very public role in the war. Traveling to Paris on family business, she made an alarming discovery.

“As I was passing through London on my way to Paris, I saw newspaper posters-Daily Mail I Think—stating that the Galway County Council was suing for peace. [In Alice’s absence a conservative faction of the council had published a resolution denouncing the war and expressing their willingness to accept peace on British terms.] When I got to Paris I saw Séan T O’Kelly at the Grand Hotel and after talking over the matter with him decided that I had better return at once, so after a few days in Paris I came back to Dublin. When I reached Fitzwilliam Place-my brother-in-law ‘s house in town- I found an S.O.S from George Nicholls, which he had got smuggled out of Kilmainham jail, asking me “For God’s sake to clear up the matter. I returned [at] once to Galway and discovered that that [sic] the whole matter was illegal, there was no quorum and so no resolution. I found out also that the peace plea had been sent to Lloyd George [the British prime minister] and others and that cur order about the lodging of the rates had been rescinded. I wrote to the papers explaining the matter, and instructed the Secretary Walter Seymour to to [sic] write to all those to whom the bogus resolution bad been sent, withdrawing the “resolution.” This was done, but the lie had a good start. and the “Galway Resolution” figures in all the accounts of the period. (see Crozier’m etc.). In my capacity as Acting-Chairman, I called an extraordinary meeting of the County Councilors and Rate collectors and I intended that at the meeting of the Council I would restore the status quo ante as to the lodgment of the rates. The Secretary, Mr Seymour, warned me that I would be arrested-and he proved right in the after event.”

For her part in rescinding the infamous “Galway Resolution” and in sequestering the rates, Alice was sentenced to six months in jail, which she spent in the company of several other famous woman rebels, including the reformer of psychiatric care Dr. Ada English, an experience she must have relished. When she was released in July of 1921, a truce between Sinn Féin and the British Government was under way. Behind-the-scenes negotiations would lead eventually to the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December of that year. Family and friends were delighted to have “Aunt Al” home from jail, but from what I know about Alice, I imagine she was eager to be back in action, truce or no truce.

By the spring of 1922, the British were mostly out of the twenty-six counties of what was now called the Irish Free State; a provisional government was in place with plans for elections and a constitution. Longstanding tensions within Sinn Féin and in the general population had turned inward. A vicious civil war over the treaty and its provisions tore the country apart from June 1922 to mid-1923. Those who had fought the British side by side during the Easter Rising and the War of Independence were now attacking and killing each other.

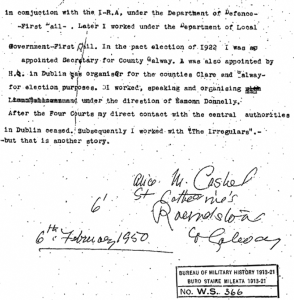

This terrible period of Irish history caused divisions that have never healed. Even today the Civil War is a sensitive and seldom broached subject, pointedly ignored in the “decade of centenaries.” When Alice wrote her witness statement in 1950, Civil War memories and grudges were still very raw. Alice took the anti-treaty position. She ends her witness statement with a brief reference to her participation in the Civil War, noting with her characteristic wry humor, “Subsequently I worked with “The Irregulars” [the “Republicans” or anti-treaty forces].–but that is another story”–a story no one wanted to revisit, then or now.

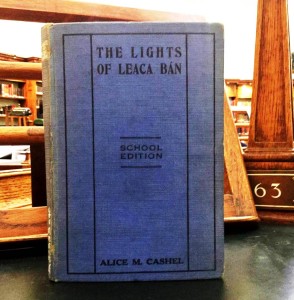

Alice had at least one more important role to play in the story of Irish independence. In 1935 she published a young adult novel called The Lights of Leaca Bán, which soon became a widely taught text in Irish schools. The version I read in the National Library of Ireland was a well-thumbed “School Edition.” The very readable but didactic tale offers a highly idealized version of the national struggle, and by extension, a vision for the new Irish state.

Set just before and during the 1916 Easter Rising, the novel tells the story of a family of cottagers in the west of Ireland who embody the virtues of a Gaelic, Catholic, Irish (not anglicized) Ireland that the government in the post independence era extolled. Family members get together for the saying of the rosary, the recounting of Celtic legends, and the singing of patriotic songs that define and reinforce their values. Rural western Ireland is presented in the novel as the true Ireland. Together they visit the western islands of Inishmor and Achill to confirm their national identity in the Gaelic speaking, peasant society enshrined there. While some family members go to Dublin for work and education, they are never content away from their spiritual home in the west, and all eventually return to that life. The novel culminates in the Easter Rising and the death of a son, who is shot fighting for Ireland on O’Connell Street. The mother declares she is glad to sacrifice her son to the cause he believed in, a sentiment the others enthusiastically approve. The last scene shows the family gathered around the dead son’s portrait singing the militaristic “A Soldier’s Song,” Ireland’s national anthem to this day.

This ultrapatriotic story fit well with the one-dimensional, nationalistic version of the independence struggle that was promoted in Ireland for decades following the events and has only begun to be challenged in the last twenty years or so, partly thanks to the release of records like the Bureau of Military History’s witness statements and the Military Archives Pensions Collection.

At the beginning of Alice’s long revolutionary career when she was frustrated at the slow progress of the Sinn Féin movement in Cork, her friend “Terry” MacSwiney—who would later become lord mayor of Cork City and die on a hunger strike protesting British rule—told her not to worry, that “the people were all right, that they were Fenians at heart.” Alice added, “Later events proved him, right, but it took a physical movement to rouse them.” The term “Fenian” refers to Celtic mythology and the Fianna, warriors who devoted their lives to the cause—in the modern usage, the cause of Irish freedom. An energetic participant in the “physical movement” to gain independence and republic status for Ireland all her life and an advocate for wider roles for women in the national drama, Alice Cashel was herself a true Fenian at heart.

Sources

Bureau of Military History. http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0366.pdf

Cashel, Alice. M. The Lights of Leaca Bán. Dublin, Browne and Nolan, 1935. National Library of Ireland.

HumphrysFamilyTree.com, The genealogy site of Mark Humphrys. http://humphrysfamilytree.com/Cashel

Christine, how wonderful. You dipped into an archive and look what you found. What a life. If only I were able to say anything remotely like, “Yes, I once transported secret documents inside my hair.” I must add, as a sometime language prof — look what can happen in your life when you’re able to speak a couple of languages! Finally, I appreciate what amounts to a primer for me on the Easter Rising, War of Independence, and the ensuing civil strife in Ireland. A few years ago, I read and fell in love with William Trevor’s novel *The Story of Lucy Gault*, which begins in 1921, and now I have a much better sense of the historical context for that story.

Jim,

I loved Lucy Gault, too, but it haunted me…still does. I am hoping to do more with the archives. And yesterday I tracked down Alice Cashel’s grave in Galway City! So exciting to have her reality confirmed in that way, sad as it was to see the neglected plot. Thanks for reading!

Just finding this page! My mom has spoken about the Lights of Lackabawn so many times. I searched online for any info on it but found nothing. Last night my nephew came across it and the correct spelling. I would like to get a copy of the book–even a photocopy of it. I am sure my 82 year mother would love to read it again. If you have any suggestions on how to track down a copy/photocopy, I would so appreciate it. Loved reading about Alice Cashel!

Hi Maura Brantley , I was wondering if you had any luck in sourcing Alice Cashels book The lights of Leaca ban . My mum used to read it to her siblings many moons ago . I would love to get a copy for her . Thanks . Anna Gallagher

The book is available at the National Library in Dublin that’s where I read it) and probably at regional libraries. I have not been successful in finding copies at antiquarian book dealers. I am told that some schools still have boxes of them in their attics or storage, so you might ask at your local school. Good luck!

Copy being listed on ebay this evening (17/06/2016)- it is the same school edition mentioned above.

I have just dicovered info relating to Miss Cashel as we referred to her Thank you .I remember Miss Cashel when i was growing up in Rounsdtone Connemara .I remember Kate o’Brien also Is there a connection with Alice &Kate?

Christine

I only came across your article yesterday and found the stories facinating. Alice Cashel was was my great grand aunt, my great grandparents were Jack Riordan and Kathleen Cashel. It was only on the last few years that I became blame aware of this part of our family history and find her fascinating while I tried to find some information I really didn’t know where to start . As a teacher myself I find it Really interesting that her book was used as a school text. I would love to know if you have any further stories about her

Thank you

Kathryn, So exciting to hear from a relative! I just sent you an email. Thank you for reading!

Hi Kathryn,

I think we are related, my grandmother was Patricia Lavelle, I remember my father talking about Alice Cashel. This narrative is so interesting, we still have strong links with Cashel, Connemara

Ena

Dear Ena,

Thanks for writing! So great to hear from descendants. I will soon be posting a revised and expanded version of the Alice Cashel story.On Easter Monday, I’m giving a talk on her during the RTE day-long celebration. I am so grateful for the comments and connections here.

Christine

Thanks Christine, I spotted your event, and am hoping to get in, finding it all fascinating. Remember my father talking about her, hope we get a chance to catch up,

Ena

That’s wonderful I look forward to meeting you. Other descendants will also be there. A family reunion!

Only saw your reply now on our way up for the talk now now as we speak …hopefully see you there …

My mother was Mary McGrath and her mother, my grandmother, was Helen McGrath nee Cashel, Alice’s youngest sister

My grandmother was Helen McGrath nee Cashel Alice’s youngest sister

Hi Everyone!

I too am searching for a copy of the Lights of Leaca Ban. My grandmother speaks of it often, and would love to read it again, however her health will not allow her to make a trip to Dublin to see it. If anyone has any advice on how I could get a copy/photocopy of it, I’d be so grateful.

Thanks,

Hazel.

I read the book when I first started to go to school. I taught myself to read when I was three – my mother always read to me and she taught me the alphabet and I just picked it up from there. The 6th class (in a country school in Co. Limerick) were reading the Lights of Leaca Ban and I borrowed it from one of them. They all laughed at me because there were “no pictures” in it – and they were struggling with the text. I would dearly love to find a copy now, for old times’ sake.

Thanks for reading! Copies of the book are hard to find. There is one available for reading at the National Library in Dublin on Kildare street. If you would like I can email you a link to a PDF copy.

Hi Christine

I have been searching for a copy of The Lights of Leaca Bán for years; my Mum says that it remains one of her favourite books. But it has been impossible to track down a copy.

She celebrates her 80th birthday in August, and a pdf of Leaca Bán would just make her year.

Paul

Paul,

Apologies–I just saw this. Are you still interested in a copy of the book?

Hi Christine , hope you are well . I wrote on this thread 4 years ago asking if anyone had any idea where there might be a copy of the book They lights of Leaca Ban . My Mum read it at school and was quoting some of it to me again today over the phone . I would love to be able to get it for her . Any information would be great . Regards Anna

Hello,

I am researching Belfast artist, Gerard Dillon(1916-1971) who met Alice Cashel in Roundstone in 1950 and according to a letter to a friend in the 1960’s stayed with her before her death in 1958. If anyone comes across any information in relation to Gerard Dillon and Alice Cashel, I would be very grateful if you would contact me.

Thank you very much for your help

Karen Reihill

Hello,

Looking at the deeds of my property in Parsonstown, Celbridge I can see that it was bought by Alice M. Cashel (of Ballybrack House, Ballybrack, Co. Dublin) in 1938 and sold again by her in 1940.

Considering she was born in Parsonstown, Co. Offaly, I’m wondering did she buy it for sentimental reasons. She left Dublin for Galway around this period.

If anyone has any information I’d be very interested!

Thanks,

Renagh Kelly

Hello Christine,

I have just come upon this site belatedly. I too have been trying to get a copy of The Lights of Leaca Bán as I have fond memories of my mother(a national teacher) reading it to me and my brothers, around the fire on winters’ evenings in the mid 1950s long before television intruded on our cosy, culturally secure lives. We were enthralled and stirred by the story which left a lasting impression. I must try again to get a copy. I am sure that the families of old national teachers will have copies on their bookshelves or in their attics.