45 Divided by a Common Language V

Posted by Christine on Apr 27, 2015 in Ireland | 1 comment

The phrases “No problem!” and “No Bother!” (sometimes “bother” is pronounced “bodder”) come up a lot in Ireland. In addition to meaning “Don’t worry, you are not causing a problem,” these phrases can also mean “Yes, I’ll do it,” as in “May we have a jug of tap water?” “No bother.” To me, such responses exemplify an accommodating attitude that I encounter everywhere here, in public and in private. I don’t like to characterize groups of people—it’s a dangerous road to go down, and you often find yourself face to face with a stereotype and a raft of exceptions. But for what it’s worth, many people who come to Ireland observe this friendly, easygoing demeanor, and I’ve heard Irish people note it as a distinctive quality.

While visiting the Rock of Cashel in County Tipperary a few weeks ago, we had a particularly knowledgeable and eloquent guide named Jane tell us lots of great stories about the thousand-year-old monument, a fortified set of ecclesiastical buildings atop a large limestone hill overlooking broad green valleys on all sides. Jane told us about the astonishing exploits of Myler McGrath, a sixteenth-century priest associated with Cashel who somehow managed to rise in both the Anglican and Catholic churches–even though they were competing for believers at the time–as well as serve in parliament, raise eight children with two wives, and occupy over seventy different clerical positions. He was both a Catholic bishop and an Anglican archbishop and no stranger to corruption. In telling us how much fun the locals have with this story in conversation today, Jane said, “We make a dog’s dinner of it, I can tell you.” Imagine how most dogs eat their dinner, enthusiastically and wrecklessly gobbling up every morsel as fast as they possibly can, and you’ll easily grasp the meaning of this wonderful expression.

Overheard while standing outside of a crowded lecture hall: “There’s not a seat left in there! It’s absolutely jammers!” Enough said.

A phrase I hear all the time comes at the beginning of a statement: “To be honest with you….” I’m not sure why it’s used so frequently in Ireland, but like “Great stuff!” (see “32 Divided by a Common Language, the Third”), the phrase serves as a verbal filler, a bridge between thoughts, a way to fill a gap as the speaker revs up for the meaty part of the sentence forming in her mind.

On more than one occasion, I have heard someone say in a weighty tone of voice, “He had drink taken.” At coffee with the women in my exercise class the other day, I learned that this is a delicate euphemism for “drunk.” The question of who is just drinking and who is drunk is often a touchy subject, especially when the person who has drink taken is a family member. The syntax reflects that of the Irish language to some extent with the past participle “taken” coming after the noun. “He is fond of the drink” is another way of saying the same thing but in a more general way. The focus is on “the drink,” not the act of drinking or the product—alcohol, whiskey, booze, or “poitín” (“put-CHEEN”), the Irish word for “moonshine.” The Irish speak of the “drinks culture” and the “drinks industry,” and “drink driving” is what we call “drunk driving.” In Ireland the legal limit for blood alcohol content is .05, lower than in the US but not as low as in some parts of the European Union where .01 or .02 are used as the standard. Ireland’s consumption of alcohol ranks below that of France, Austria, Estonia, and Germany but is still fairly high. I have observed lots of angst about the country’s reputation for drinking that is awkwardly balanced with advertising campaigns for Guinness and other beverages and attempts by the tourist industry and the government to sell Ireland’s pub culture.

Bushmills in Northern Ireland is the oldest continuously producing whiskey distillery in the world. Known as “Protestant whiskey,” Bushmills is happily consumed by even staunch Republicans.

Speaking of “the drink,” do you know why it’s Scotch “whisky” and Canadian “whisky” but Irish “whiskey”? I learned about all of this at the Dingle Whiskey Distillery, Ireland’s newest and yet most traditional of Irish whiskey distillers (see photo at top). First of all, the word “whisky” or “whiskey” comes from the Irish word for water “uisce,” pronounced “ISH-ka,” not a far cry from “whisky.” The Latin word for alcohol was “aqua vita” or “water of life.” In Irish Gaelic that became “uisce beatha” (“ISH-ka BAH-ha”) and in Scottish Gaelic “uisge beatha,” lively water” or “water of life,” eventually morphed and shortened in English to “whisky.” As a translation, I like “lively water.” Some believe that the “e” in Irish whiskey—and, through the influence of immigration, American whiskey—is simply a regional variant of “whisky” that has become standardized. Canada, Scotland, and Japan all stick with “whisky.” Another theory says that the “e” was purposefully introduced to distinguish the Irish product when Scotch was taking over worldwide sales in the twentieth century. In any case, Irish whiskey and Scotch whisky are immutable terms now. Even The New York Times, which used to use “whiskey” for all products, has agreed to honor the spelling distinction. Both the Irish and the Scotch versions of these barrel-aged spirits use malted barley as the basis: Irish whiskey is triple distilled, making it smoother, while Scotch whisky uses peat fires in the malting process to impart a distinctive smoky flavor and is distilled only twice. The debate about which approach to making whiskey/whisky produces a better drink rages on, and you’ll have to do your own research in order to determine where you stand on the matter.

My friends at the gym recently set me straight on one important definition. They were talking about Irish politicians and the phrase “carrying on” kept coming up. While I could pretty much define that one for myself given the context, one of the women turned to me and said “Do you know what we mean? ‘Carrying on’ is always sexual!’” Point taken.

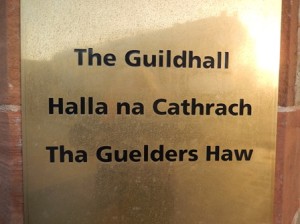

“Would you like a wee biscuit with your wee coffee?” This “wee” word comes up a lot on conversation in Northern Ireland and in the northern counties of the Republic, as it does just across the water in Scotland. Northern Ireland has a historical, cultural, and linguistic kinship with Scotland, which is after all only twelve miles away at the closest point and can be clearly seen on most days. Scots settled northeastern Ireland in large numbers over the centuries, becoming the “Ulster Scots” and providing the United States with a significant number of presidents (one count says seventeen) through that ancestry. “Ulster Scots” is a form or dialect of “Scots,” a language that is sometimes confused with Scots Gaelic or Gallic but derives from the same linguistic ancestor as English and is spoken by more than thirty percent of Scottish people, mostly at home. There is a movement in Northern Ireland to revive this language and have it recognized in schools and on signage. Because of this shared language history, many people can’t tell the accented English of Northern Irelanders from that of the Scots.

In Northern Ireland as in Scotland, everything is “wee,” which means small, but also functions as a kind of verbal emphasis and filler. “Would you like a wee drink?” isn’t an offer of a small drink but suggests that having a drink would be a good thing and won’t take you much time or give you much trouble. Or it can simply be a way of stretching out the sentence to make it sound less abrupt, more polite. “Wee” is not, after all, a Scots word but an Old English one. Here is what the Online Etymological Dictionary has to say:

Wee “extremely small,” mid-15c., from earlier noun use in sense of “quantity, amount” (such as a littel wei “a little thing or amount,” c.1300), from Old English wæge “weight” (see weigh). Adjectival use wee bit apparently developed as parallel to such forms as a bit thing “a little thing.” Wee hours is attested by 1891, from Scottish phrase wee sma’ hours (1819). Wee folk “faeries” is recorded from 1819. Weeny “tiny, small” is from 1790.

One of our favorite usages of “wee” came from our hosts at the Valleyview Country House bed and breakfast in Bushmills, Northern Ireland (where we also toured the eponymous whiskey-with-an-e distillery). Valerie and Maynard were fantastic hosts, and we liked this place so much we’re going back in May. In addition to running the business with his wife, Maynard also has a herd of cows in the pasture out front. Valerie, using the Ulster Scots word for “cows” referred to them as the “wee coos,” a usage proving once again that “wee” doesn’t always mean “small.”

The Gaelic language shapes Hiberno-English in ways that are both obvious and subtle. For example, an Irishism that is often parodied is the use of “after” as in “I’m after writing a letter to him.” This usage reflects a Gaelic way of referring to the past. “After” or “tar éis” in Gaelic locates the statement in the recent past, as in “tá mé tar éis é a fheiceáil lú ná cúig nóiméad ó shin,” “I’m after seeing him not five minutes ago.”

In a similar vein, you will hear the words like “myself” and “himself” often in Hiberno-English because in Gaelic there are special words used to achieve that kind of emphasis, which in English we often produce with the voice only. If you were to tell me your name, I would respond by saying “Is mise Christine,” which means “My name is Christine,” or “I am Christine,” emphasizing that now it’s my turn to tell you my name. “Mise” (“MEE-shuh”) emphasizes the first person singular, and similar words exist for the other personal pronouns. The phrase for “man of the house” in Irish is “sé féin,” literally “himself.” So if I were to say “Himself came home late from work” you would understand me to mean “Ron came home late from work.” Today “himself” or the equivalent “herself” used as the subject of a sentence can indicate a joking or satirical attitude towards the subject. But I would never do that.

Especially in the southwest of Ireland, you may here the phrase “right so” or “right” or “so” by itself, often at the end of a sentence. “I’ll be going to the shop, right so.” Or “Shall we have a drink, so?” These words or their combination offer a subtle form of emphasis, a question not expressed as a question that also doesn’t require an answer. “I’ll be going to the shop, then” or “I’ll be going to the shop, okay?” are two ways of glossing the phrase. In American English we often use the interjection “right” after a statement. We’re not always asking for overt affirmation, but the “right” provides a pause, an emphasis, an opening for the person you’re talking to. “Right so” can also indicate a readiness to finish one subject and move on to the next subject or action. Right so?

Not that this applies to me, but when you’re buying movie ticket or paying for admission to a museum in Ireland, you will see the option “Concession” in the list of prices. It means “senior discount” and refers to the fact that the government is granting this reduced price to senior citizens. “Two concessions, please.”

At the end of a conversation in a shop or with a friend, you might hear the parting words “Mind yourself!” The equivalent of “take care” but somehow livelier and warmer, this phrase is a great way to say goodbye. “Mind” meaning “take care of” is just more common in Ireland than in the US.

I’m after finishing this post now. I hope you find a way to make a dog’s dinner of it. I’m going to take a wee break and have a wee dram of whiskey, which I prefer to whisky, right so. Mind yourself!

Still laughing about “wee coos.” I think what I like best about your blog these days is that it gives me the opportunity to relive our trip there. When we returned, many asked about the pub culture in Ireland and specifically asked which pubs we had visited. Of course, my response was more about graveyards, abbeys and castles . . .