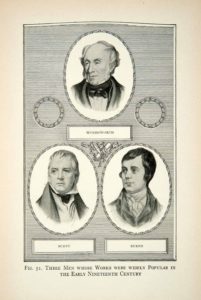

When you saw the prospectus for our trip, you probably said to yourself “Burns? Scott? Who reads them these days?” I have an answer for your doubts, but only if you’ll expand in your mind the meaning of the word “read.” Hang on though, because it will take me a minute to get there.

First of all, you are stuck with a literature person as your “group leader.” I hesitate to use that term, but please know that at some shopping locations abroad, group leaders get sizable discounts. And with the right number of trip participants, group leaders’ airfare and sometimes hotel are gratis.

I’m no expert on either Burns or Scott, but I studied them both in college and graduate school, and my dissertation, “The Magic Circle: Elizabeth Inchbald, Mary Hays, and Mary Wollstonecraft and the Politics of Domestic Fiction,” was an attempt to prove that Scott did not invent the historical novel entirely on his own, as many critics still claim. I love Scott’s novels, and I respect his efforts on behalf of his beloved Scotland, but the evolution of the novel is far more complex than “Scott invented the historical novel.”

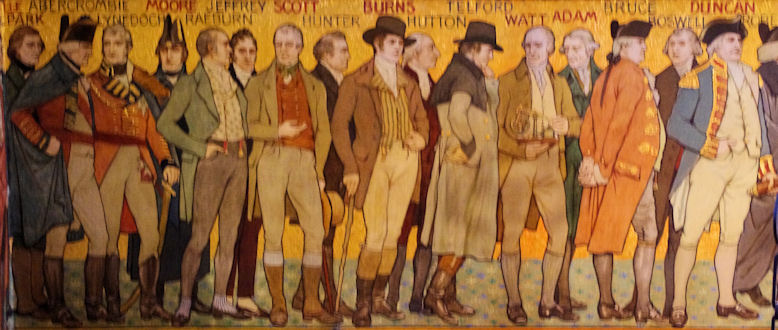

Even more important, without Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, Scotland wouldn’t be what it is today. Each writer in his unique way contributed substantially to the creation of Scotland in the modern imagination. Interestingly, both writers reached into the past to do this.

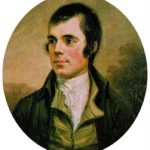

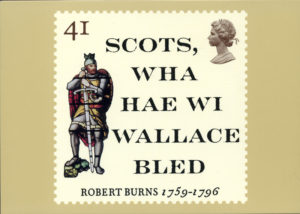

Burns led the movement to preserve Scottish folk songs and their accompanying culture. He saw himself as the inheritor of a tradition, not an inventor of one, and relished being called Scotland’s “bard” in the old style. Back in the day, bards were much more than poets. They preserved the cultural through story and song, created and  protected their patron’s reputation, and served as chief historian to the community. Burns lived in a time when Scotland’s identity was being swallowed up by Britain, and when the juggernaut of English was wiping out dialects and languages locally and all over the world (still true today). Because he wrote so many of his poems and songs in his native Lowland Scots or “Lallans,” as it was called in Ayrshire, Burns also helped preserve the old language.

protected their patron’s reputation, and served as chief historian to the community. Burns lived in a time when Scotland’s identity was being swallowed up by Britain, and when the juggernaut of English was wiping out dialects and languages locally and all over the world (still true today). Because he wrote so many of his poems and songs in his native Lowland Scots or “Lallans,” as it was called in Ayrshire, Burns also helped preserve the old language.

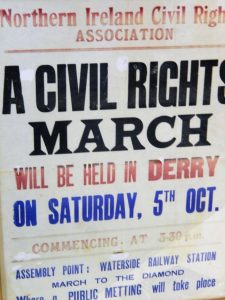

Speakers of Scots today, whether in Scotland or Ulster, cherish Burns’s work, celebrating it both by performances and by educating the next generation. Today Scottish school children still learn to recite Burns’s poems, honoring the literature of their mother tongue. In Northern Ireland speakers of Ulster Scots or Ullans, a branch of Scots, teach Burns’s poems and songs in the schools under the auspices of the Ulster-Scots Agency (which we will visit when we’re in Belfast). With his love of natural settings, his command of language and rhythm, and his deep understanding of human nature, Burns makes a valuable and engaging study.

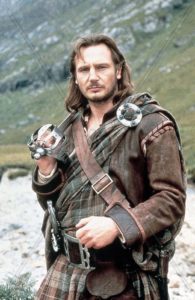

Even more purposefully than Burns, Scott sought to preserve the history and legends of his homeland in the poems that made him famous and in the novels he churned out during the second half of his career. In the novels, he brought forward past heroes of independent spirit, like Rob Roy, and invented others to serve as model Scottish men, and he populated the novels with an amazing and lively array of characters–a strategy we call “Dickensian” today. He also set about reviving the culture of the Highlands, which had faded from public attention as the Highlanders were driven north and persecuted. He saw the oppressed Highland people as Scotland in embryo. In his writing and in his life, he fueled the surge of interest in not only the ethos and culture of the Highlands but also the distinctive Highland style of dress: tartan, kilt, sporran, kilt pin, clan badges, glengarry bonnet, ghillies, and all.

Scott participated enthusiastically in the newly invented “tradition” of associating one tartan design with a particular family or class (previously tartans had reflected only regional identity) and helped make the trend all the rage. When King George the IV visited Scotland in 1822, a very grand shindig engineered by Scott, the celebrity author persuaded the king to appear in full Highland dress. It is said that for the famous painting of His Majesty in this costume, the artist SIr David Wilkie replaced the monarch’s bright pink tights with elegant knees and socks. He also modulated the dazzle of the jewels, the brightness of the kilt, and the fat on the royal person.

It is interesting to note that Burns and Scott both came from the band of Scottish territory closest to Britain, where English ways and English authority easily penetrated. There was more intermingling and more intermarriage here than in the more northern reaches of the province. Did this nearness to the great foe of centuries make the need for a Scottish identity more intense?

In any case, Burns and Scott were part of a larger nationalistic movement sweeping Europe that would erupt in self-defining revolutions and rebellions for a century to come. The Scotland they dreamed of, wrote about, and celebrated is the Scotland we know today.

The answer to your doubts about these two literary giants depends on the meaning of the word “read.” No, people don’t read much Burns or Scott these days if you’re talking about picking up a book, and more’s the pity. People around the world encounter Burns every time they sing “Auld Lang Syne,” of course, or any one of the dozens of songs he penned. And his words and insights creep into our language every day without our noticing (click Robert Burns in Our Daily Language for a short list of just a few common Burnsian sayings). Burns clubs ring the globe, and knowledge of his work is far more widespread than is generally credited.

For his part, Scott revolutionized the novel’s form by using it to retell the past and popularizing the technique. Would we have Wolf Hall, I, Claudius, or A Tale of Two Cities without his bold and voluminous example? Though he would not have supported an independent Scotland, he built the foundation upon which the independence movement rests by giving Scotland’s its history–separate from England’s history–albeit fictionalized to glorify a certain ethos. And don’t forget, until that other Scot J. K Rowling came along, Scott reigned as the world’s most most famous writer.

To read Scotland, to read the novel as it has evolved in our day, to read the reading mind of the world’s people, to read the human heart, you can do no better than to read and study Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott.