44 Graveyards, Graveyards, and More Graveyards

Posted by Christine on Apr 20, 2015 in Ireland | 4 comments

During a Christmas trip to Dublin I hosted for my brothers and their families in 2001, they all accused me of only taking them to see “prisons and graveyards, prisons and graveyards.” I must confess that they were right. On that trip family members flew in from all over the US to meet for the first time at Kilmainham Gaol, a grim and very cold prison built in the 1790s that housed many political prisoners and that in 1916 saw fourteen of the infamous executions of the Easter Rising. Over the next five days, we visited a magnificent five thousand year old ceremonial tomb, several tumbledown graveyards at ruined monasteries, a pet cemetery at Powerscourt Estate, and a few miscellaneous graves and graveyards along the way. Since we actually visited only one prison on that trip, albeit a very daunting one, it would have been more accurate to sum up our itinerary as “graveyards, graveyards, and more graveyards.”

Not counting churches, most of which have people buried inside them, but including Megalithic tombs and ruined monasteries, there are at least eight or nine graveyards on the itinerary for the student trips to Ireland I lead every two years. During this sabbatical year spent in Ireland, our visitors will no doubt confirm that graveyards have figured in our sightseeing with them to an abnormal degree. And without my intending to go in this direction, four of my blogs have been exclusively about graveyards: Jerpoint Abbey (“10 In our arts we find our bliss”), remembering the dead of World War I (“21 Remembrance”); Yeats’s famous grave at Drumcliff Churchyard (“33 Under Ben Bulben”); and Cromwell’s cabbage garden turned cemetery turned city park (“36 The Cabbage Gardens”). I freely admit to having an obsession, but the accidents of history and geography have also played a part in making cemeteries an important theme in the Emerald Isle.

This is a country of graves. Ireland’s long history of human habitation (since at least 8000 BCE), small size (Ireland is smaller than the state of Georgia), preponderance of rocky and boggy land unsuitable for burials, and island status mean that here the dead compete for space with the living. And in addition to the regular graveyards, everywhere you go you see monuments and inscriptions commemorating those who “died for Ireland”–at their birthplaces, their schools, their places of work, the places where they died, and so on. Ireland’s perpetual “underdog” or as some might say “loser” or “defeated” status adds special importance to the glorification of the dead, especially those who fought to achieve Irish nationhood and failed. Irish history is, in one sense, a centuries-long list of failed rebellions. “We love our failures!” or words to that effect is something I’ve often heard said here. And there’s no better place to contemplate that sad history and its eventual glorious outcome than at a grave or a monument to the dead.

Graves are about all that remains of the earliest settlements on this island, so places like Newgrange, the Hill of Tara, Carrowmore, and Creevykeel figure in most tourists’ itineraries. We think of these iconic structures as monuments rather than cemeteries, even though ancient remains have been found at all of them, and at all of them huge rocks and mounds of earth were moved across rough countryside and piled high to honor the dead. Little is known about the lives, beliefs, and burial practices of the Megalithic period, but it seems certain that great effort, skill, and ingenuity spanning generations were necessary to build these tombs and earthworks, and that powerful beliefs motivated their construction. Whatever else these places are, they are certainly graveyards.

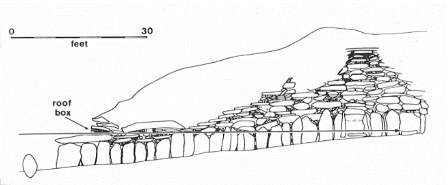

A diagram of Newgrange showing how the light from the sun at the winter solstice (long arrow) enters the roof box opening and illuminates the floor of the triple chamber

At Newgrange, an intact passage tomb older than Stonehenge about thirty-five miles north of Dublin, the resources of a large community over several generations were committed to honoring the dead. In addition to being a place for ceremonial burial, the tomb was constructed so that on the winter solstice, light from the rising sun would stream in through a small “roof box” to illuminate for seventeen minutes the triple chamber inside where the ashes and bones of the dead were found. The corbelled stone roof of the tomb, still in place and watertight after more than 5000 years, weighs an estimated 200,000 tons, and the tomb is surrounded by ninety-seven “kerb” stones, each weighing several tons. Whatever the rising sun had to do with the dead buried here, it must have been a very powerful connection to have caused so many people to work so hard to bring those stones from locations thirty or more miles away, drag them up the hill, and build the tomb over several decades at least with utter precision. There are thirty-five other smaller passage tombs in the area surrounding Newgrange and more scattered across the island, further testament to the power of the dead to shape the lives and determine the destinies of the living.

Agnes Scott students at Glendalough, “Glen of Two Lakes” founded by St.Kevin in the sixth century CE

In Ireland graveyards occupy some of the most beautiful places–real estate of high value and importance. The old graves with their elaborate headstones, faded inscriptions, and Celtic crosses are far more interesting than the slab upon slab design of modern cemeteries, adding to the romantic lure of these sites. Glendalough, or “glen of two lakes” set in a secluded valley in County Wicklow is really a monastery more than a graveyard, but the wishes of people over 1400 years to be buried in the monastery’s holy ground have turned it into a most compelling burial place. The same is true of other monastic sites such as Monasterboice in County Meath, Clonmacnoise in County Westmeath, or the Rock of Cashel in County Tipperary–all active cemeteries, though the number of available plots is limited to members of families already interred there. We go to see the dramatic settings, ruined buildings, fine carvings, and religious imagery, but in truth the graves give these places their continuing relevance and enhance their other-worldly atmosphere.

Visiting the graves of writers, political leaders, and other famous people gives you a moment to reflect on their accomplishments and their failures and perhaps pay your respects. Observing how the grave honors the dead is a history lesson in itself. Fourteen of the sixteen leaders of the Easter Rising (1916) are buried in Arbour Hill Cemetery, a former military barracks not far from Dublin City Centre but not well known, even today. Following the executions of these men, the British army buried them in quick lime in a mass grave here hoping futilely, as it turned out, that they would not be honored as martyrs. In preparation for the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising the Irish government, led in part by some who had survived the rebellion, saw to it that the grave was turned into a more fitting memorial, naming the men in English and Irish and creating as a backdrop for their graves a wall with the “Proclamation of the Irish Republic” that they fought to fulfill engraved in Irish and English. For diehard Republicans, Arbour Hill is holy ground, and they hold a solemn memorial every Easter to remember the “martyrs.” The centenary of the Easter Rising in 2016 will no doubt add still another layer to the history of the graves at Arbour Hill.

A Republican ceremony at Arbour Hill Cemetery for the leaders of the 1916 Rising on Easter Monday 2015. The fourteen men are buried in a common grave marked with their names in Gaelic and English.

The most interesting graveyard in Ireland, Glasnevin Cemetery in north Dublin, is unique for the sheer number of famous Irishmen and women buried here and for its stunning size–with 1.5 million buried there, it has a larger population than the city of Dublin. The cemetery’s founder, Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847), known as the Great Liberator, fought to free Catholics from the restrictive penal laws that prevented them from voting, holding office, owning property, and much more. Having achieved Catholic Emancipation in 1829 through oratory and what we would today call “community organizing,” he turned his attention to repealing the Acts of Union that bound Ireland under British rule and the abolition of slavery among other causes. It was O’Connell’s dream that Ireland would have a great cemetery where people of all faiths or no faith could be buried together, and so he established Glasnevin in 1832. His vision for the place ensured that Glasnevin would draw more of the famous people in a country’s history than perhaps any other single cemetery in the world. Fittingly, O’Connell’s tomb is the most prominent here, with a round tower rising above the recessed vault and a stone sarcophagus encasing his wooden coffin, which you can touch through the gridwork for luck.

At Glasnevin you can pay homage to Roger Casement (1864-1916), hanged by the British for treason in 1916 for running guns to support the Easter Rising; Brendan Behan (1923-64), the great playwright and novelist who drank himself to death; Maud Gonne (1866-1953), actress, revolutionary, and object of William Butler Yeats’s unrequited love, who inspired many of his greatest poems; her son Seán MacBride (1904-88), who cofounded Amnesty international and won the Nobel Peace prize for his work; and Eamon De Valera (1882-1975), Easter Rising veteran, founder of the Fianna Fail political party, and “taoiseach” [TEE-shook] or prime minster for many terms, who as president of Ireland hosted John F. Kennedy during his October 1963 visit to his ancestral home. The English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89, author of “Pied Beauty” and “Spring and Fall”) is buried here in the Jesuit Plot. Because the cemetery kept meticulous records over the years, the guides will also show you the unmarked plots where children, soldiers who served in Irish or foreign wars, poor people, and others were buried without gravestones.

My favorite grave at Glasnevin is that of Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-1891). A protestant member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, County Wicklow estate owner, and representative for Ireland in the British parliament, Parnell nevertheless devoted his life to achieving land reform to benefit the Catholic underclass and Home Rule, a kind of dominion status that would have given Ireland a degree of independence in the nineteenth century. Brought down in a scandal surrounding the divorce of his great love, Katherine O’Shea, whom he eventually married, Parnell died at 44, the hopes of Irish independence dying with him, at least for a time. He was called “the uncrowned king of Ireland” and widely revered. His grave is a stunningly simple boulder of Wicklow granite with “Parnell” inscribed on it sitting alone in a grassy expanse that also marks the burial of hundreds of cholera victims of an earlier generation. Parnell had wanted to be buried with his people.

The grave of Michael Collins in Glasnevin. The card from Veronique can be seen just behind the wreath.

Glasnevin is full of the heroes and villains of various revolutionary efforts, with those who opposed each other in life often lying close together in death. By far the cemetery’s most famous grave is that of Michael Collins (1890-1922), a remarkable figure whether you love him or hate him, and these factions argue about his legacy to this day. Collins was a military genius credited with inventing modern guerilla warfare, a leader in the War of Independence, and head of the provisional government that took over when the British pulled out in 1922. Later that year during the bitter civil war that followed independence, he was killed in an ambush in his native County Cork at an obscure place called Béal na Bláth [BAIL-nah-BLAH]. He was thirty-two years old. The country was stunned, and hostilities were temporarily suspended as both sides mourned his loss. It is estimated that 500,000 people or one-fifth of Ireland’s population attended his funeral as the cortege wound through Dublin city streets and out to Glasnevin. The footage of the funeral testifies to the impact Collins had on Ireland, then as now.

The tours of the cemetery always end at Collins’s grave, perpetually heaped with flowers and bottles of beer and whiskey from besotted admirers. Every Saturday, members of a local group come to tidy the grave, put the flowers in vases, and and tend to Collins’s memory. A woman from France has made headlines with her regular pilgrimages to the grave and her constant floral tributes; she visits the grave four times a year, sometimes bringing friends, and sends flowers on holidays and other occasions, too. When I was there in December, an elaborate arrangement of flowers from her was delivered to the grave as the tour group stood there watching; the card in the arrangement read “To Michael, Happy Christmas and lots of love, Veronique XX.”

If you stay long enough in one place or visit often enough, sooner or later you encounter graves of people you knew. Shane MacThomáis–for many years synonymous with Glasnevin Cemetery–was the son of the famous Dublin guide and historian Eamonn MacThomáis (1927-2002). Like his father, Shane was a superb storyteller, witty and knowledgeable, passionate and thoughtful about history, and a staunch Republican.

I met Shane in 1998 on the first Agnes Scott trip to Ireland. He gave us such a fascinating, funny, and enjoyable tour of the cemetery that I requested him on every subsequent trip and told my friends traveling to Ireland to make sure they got him as their guide. His crackling wit lit up a dark rainy winter day in the graveyard like nothing else could. He knew everything about Glasnevin and was a major force in arguing for the renovations that brought renewed respect to the lives of those buried here and made this place—a cemetery—the number one tourist attraction in Ireland. His love of Glasnevin was his profession and his passion. I remember asking him about the whereabouts of the graves of a couple of my favorite Irishmen—Seán Lemass (1899-1971) , the taoiseach who brought Ireland into the modern world, and Douglas Hyde (1860-1949), Gaelic language activist and first president of Ireland. “Ah, I really wish I had them here,” he said.

On March 20, 2014, Shane was found dead in Glasnevin Cemetery, a victim of suicide, or so it was said. He was forty-six. Shane had a remarkably open and generous mind, and in his job as Glasnevin Cemetery historian, made sure that every person and every story buried there got the respect that was deserved. Though his family had a long tradition of Republican politics and Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams gave the eulogy at his humanist funeral held in Glasnevin, members of paramilitary groups on the opposite side of Irish politics attended Shane’s funeral in an unprecedented crossing of party lines.

Shane is buried with his father, not far from the visitors center where his cemetery tours began. The inscription on his father’s headstone read “patriot, historian, writer, Dubliner,” words that apply perfectly to the son. So when Shane’s name was added, the nouns commemorating his father were simply made plural. I’ve added Shane’s grave to the long list of graveyard pilgrimages I make whenever I come to Ireland.

Did you forget to include that special church graveyard in Arigna? I believe the great-grandparents of a friend of yours is buried there.

That graveyard expedition deserves a whole story unto itself–written by you!

Oh, this is a wonderful post, Christine. Once again, I feel that I am learning the history of Ireland via a blog post that is ostensibly about something else. As a student of ancient history, my eye is drawn especially to your description of Newgrange, but it’s all a treat. Imagine being able to visit Glasnevin and see ALL those famous names. Your readers may be interested to know about the 2014 film concerning the cemetery, “One Million Dubliners.” Apparently a sensation in Ireland. Shane appears several times in the trailer, which is available on You Tube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIb3p5TKSA4. I’m on a mission now to see the entire film, having wept openly just watching this trailer and hearing Shane say to the camera, at the end, “It lifts my spirit to work here.”

Thanks Jim! It truly is a wonderful film–we have it on DVD and I’ll lend it to you when I’m home. Knowing Shane as I did, I started crying as the film opened and didn’t stop until it was long over. When I revise the piece, I’ll link it to the YouTube clip–didn’t know it was on there, so thank you for that, too!